It’s now 117 years since the birth of Billy Wilder on June 22, 1906. I had the good fortune to interview the great writer-director of the classics Double Indemnity, Sunset Blvd., Some Like It Hot, The Apartment and so many others in his office in Beverly Hills on September 17, 1993, the first of six encounters (two in person, four by phone). He had been informed that I was contracted to write a biography/critical study of him for the publisher Henry Holt and Company, and somewhat grudgingly agreed to sit down with me. According to his agent, he joked, “If Rabin and Arafat can shake hands, I suppose I can meet with Mr. Lally.” As our session began, Wilder made it clear that he was more than willing to be open and cooperative, as long as I was “serious.” Here, published for the first time, is the partial transcript of our first meeting. If the conversation seems to jump around erratically, it’s because there was so much ground to cover. One of the proudest moments of my life is when, as my allotted time wound down, Wilder announced, “Mr. Lally, you have another hour.”

The conversation begins with Wilder explaining…

If you make children, not every one of them is going to be 100 percent to your satisfaction—there’s going to be some disappointment. And if it’s a late bloomer, like some of my pictures that have been forgotten and now are being shown again thanks to television, there’s some excitement about it, realizing they were done 30 or 40 years ago. I have withstood all of that, and as long as you have a serious approach, be it critical or not, be it justified or not, it is welcome, believe me.

Thank you. I have a present for you [a record by American bandleader Paul Whiteman].

He was just about the first American I ever met in my life. The year was 1926. I had become a newspaper reporter of the lowest rank on a paper in Vienna. Whiteman was in Europe and he was giving four concerts: The first part was the big, standard hits, and the second half was Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.” He gave concerts in London, Paris, Berlin and I think in Amsterdam. He was in Vienna—he was not giving a concert there—and I interviewed him with my lousy English. A guy in his group kind of liked me, and I said, “Gee, I wish I could go to the concert in Berlin, but there’s no way anybody would pay my ticket to Berlin.” In those days, I did my reportage on foot or by streetcar—nobody had an automobile, only the publisher. So I went to Berlin on the invitation of Whiteman, and I never went back to Vienna. I stayed on as a newspaperman and I started helping people with screenplays—what they call a Negro, the German word for ghostwriter, somebody who’s very popular, with three scripts to write at the same time. Ghostwriters would do considerable work without getting any credit. There’s a joke I heard the other day: A writer is stuck with a script, and suddenly a genie appears. He says. “I’ve been watching you, is there anything I can do?” He goes away, and comes back with a complete screenplay. The writer says, “That’s great,” and he’s nominated for an award. The second time, the writer can’t lick a story, and it’s due the following Monday. The genie appears again, and comes back with a complete screenplay. The third time, the genie says, “You know, I’ve done a lot of work for you.” The writer says, “Well, you can have anything you want, I’m so goddamn grateful.” And the genie says, “Could I have co-writer credit?” And the writer says, “Fuck you!” That’s the story of the ghostwriter. A good ghostwriter has talent and ideas, but equally important is to keep your mouth shut.

We’re talking about things that happened more than 60 years ago. Only after all those years do I say, “Yes, I had something to do with that picture.” They took enormous advantage: In those days—they would get 50,000 marks for a screenplay, and I would get 250 marks a week. But once I opened my mouth, I would not even get a job as a ghostwriter.

I’ve seen so many different figures for how many screenplays you worked on in Berlin…

[Wilder misunderstands my question.] Basically, I had two collaborators over a period of more than 15 or 20 years—[Charles] Brackett and I.A.L. Diamond. If he were alive, Diamond would be sitting where you’re sitting now. He died, and it was a tremendous sledgehammer blow. We had developed this Esperanto language between us—I knew what he meant, and he knew what I meant, and there was no ranking like in the Army. Most of the time, I would be standing and writing on my yellow tablet, and he would be sitting at the typewriter. If I came up with something, and he said I don’t think it’s right, or he came up with something and I said it wasn’t working, without any anger we would just tear it up and work again and again until both of us loved it.

I asked Barbara Diamond [Diamond’s widow] why the two of you worked so well together, and she said her husband had tremendous pride but no ego.

No ego. He was absolutely irreplaceable. I cannot get myself organized—I don’t know anybody I would like to work with. I started the idea of collaborating when I first arrived in America because I could not speak the language. I needed somebody who was responsible, who had some idea of how a picture is constructed. Then I found out that it’s nice to have a collaborator—you’re not writing into a vacuum, especially if he’s sensitive, especially if he’s ambitious—and by ambitious, I don’t mean your standing in the community, but that the product has some value. When people walk out of a theatre, they should leave with something more than just having seen a two-hour-long film.

But I’ve been doing other things… I am a collector over very wide-ranging areas. I had a big, very good collection which went to auction at Christie’s in the fall of 1989. That did not mean it was the end of my collecting mania. I have started new collections of various things, and sometime in November I’m going to have a show at the Louis Stern Gallery of things I’ve collected, objets trouvés, things that I have done myself or in collaboration with somebody.

[We’re briefly interrupted by a phone call, and the subject turns to modern movies.]

Those ugly things which are very, very necessary and make people extremely rich—I’m talking about special effects—I can’t do that, I can’t direct car crashes… But slowly now, I have a feeling people are coming back to the content of a picture, to the exploration of a character a little bit more in depth. By this time, as far as plots are concerned, I think we’re done. Now we’re doing remakes. There’s a picture of mine called Double Indemnity—they remade it five times, but none of those is any better. Why don’t they show the original? Let them do the Jurassic Parks, that’s fine. But with all those millions that they make, they should put a small sum aside and let talented people make pictures for a million or two million.

As you know, today anything goes in movies. I’m interested in some of the censorship problems you ran into when you first started working in the studio system.

When I said I thought I could make a picture out of Lost Weekend, by that time I had already had my credit established with the front office at Paramount. I’d made Double Indemnity, which was actually brought to my attention by a young producer by the name of Joe Sistrom. They wanted to only give him the credit of associate producer, but I said, “No, he was the producer!” He was responsible for getting the studio to finance the picture. It was extremely difficult to get a leading man [to play] a murderer, nobody wanted to play that. I had to talk Fred MacMurray into it—it took me days! He said, “My God, this requires acting!” I said, “Yeah, it does require acting, I know what you mean, but you have the kind of personality that you just have to behave. You don’t have to act, just behave.”

Was it frustrating for you as a writer to have to keep submitting drafts to the Production Code Administration?

You mean censorship? Lubitsch, for instance, totally ignored whether the censorship was strict or lax. I don’t remember ever having seen a nude scene in a Lubitsch picture, nor a scene where people are rolling in the hay. Now you go see a picture, and already under the titles there is coital action—under the titles! My wife would say, “I think that is his left knee.” I’d say, “No, that’s the right breast.” But he never got himself in that position. His mind did not work in that direction. He would tell you enough to titillate you—he would tell the audience there was sex last night by only photographing the way the couple attacked breakfast, the way they looked at each other, the way they broke a croissant. A kiss, yes, but never, ever… There was that old rule that even if the two leads were married, they could not sleep in the same bed, and if he kissed her, one of his feet was to be on the ground, this kind of crap. I’m against any censorship whatsoever—it’s my nature, I grew up like this, the First Amendment is very precious to me—but what happened unfortunately is that the pornographers jumped on this new freedom and they could not get enough. But the audience got enough—they’re very bored with it now… It is not erotic and it does not work unless the audience is [involved] with the lovers in bed. Lubitsch let you know what happened, and it could not be censored—you could not put your finger on it. We also had to use different language: You could not say “bastard,” for instance. We invented little detours: “If you had a mother, she’d bark.” They’d add it up: “Oh yeah, son of a bitch, that’s what they meant.” The Hays Office or the Breen Office were just too dumb to object.

I’d like to know how you got away with the things you did in A Foreign Affair [1948]. Here you were—

The affair with the German girl? They were not in bed. Of course, he did the swap the cake that his fiancée in Iowa sent him through Jean Arthur, he swapped it for a mattress because he could be having Marlene [Dietrich] but there was no bed to be had. But driving a mattress in his jeep through the destroyed Berlin—there’s nothing censorable in that. An American officer, a German girlfriend—corrupt—and a mattress. A man doesn’t want to go sleepless in Seattle. We just got away with it. There were very few times where I had to cut something because I lost a battle. I was not laughing behind their back—”Ha, ha, ha, they don’t know what I did”—no. I have my own censorship that tells me this is ugly, this is schmutzig, this is dirty, it’s not worth it, it degrades the picture, it degrades the writer and director—don’t do it. Easy laughs or easy sensational moments. If you are wondering how I got away with that, how did the Italians get away with The Last Tango in Paris?—I was not even in the same neighborhood, not even on the same planet! You remember when Miss Pauline Kael—somebody quoted it again because he did not like me—said that when she saw Sunset Blvd., it made her puke. And I always wanted to ask her, “How did you feel about that butter job in The Last Tango in Paris?” Mr. Ber-to-lucci—I kind of admired his nerve, because I could not even tell that to the front office.

Going back to A Foreign Affair, did you hear back from the Army and the government about the image of them you were portraying?

No, because I was in the Army and I was in Berlin. If they would have told me, I would have said. “All right, this is fiction, but let me tell you things that I observed that are absent. It is not just the American or the Russian occupiers that behave like this. Every occupying, victorious army rapes, plunders, steals—that is a rule that goes way back to the Persians.”

[We’re interrupted by a call from an Austrian official]

I’ve noticed in interviews that you don’t always have the kindest things to say about Austria.

About Austria, no. There are many aspects to Austria. There’s Mozart, but there’s also the guys that killed so many. It’s a small country—seven and a half million, of which two and a half million are in Vienna. It’s like a baby with an enormous head. But I think that the Tyrol and the various small states that make Austria what it was—not what it was, because what it was was a country of 56 million people, with parts of Czechoslovakia, Poland, where I was born, Hungary and Yugoslavia. Let’s not forget that the Crown Prince at the time of Franz Josef, Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo. I think that in the province Nazism is strong, has been stronger than the German Nazism. Let us not forget that Mr. Hitler was Austrian. As they say now, the Austrians are absolute magicians—they have now convinced the world that Beethoven was an Austrian and Hitler was a German. I always get into terrible fights with the newspapermen, because I remember my days in school. I remember the attitudes. The most famous Austrians, whether it be Schnitzler or Mahler or Schoenberg, they were Jewish. The source of anti-Semitism, the bloodline, is the lack of education. It is impossible to eradicate, it was impossible to do it 2,000 or 4,000 years ago. They were always on the march.

In Spain, at least, Torquemada said that the Jews would be sent to death unless they became Catholics. They had a choice. In Germany, there was no choice, if just one of your grandfathers was Jewish. So I have my misgivings—I hate to go to Vienna… I guarantee you there will be a thousand people outside the hotel screaming, “Get the Jew out.” Don’t write that, please. I have constant feuds with Austrian newspapermen. On the other hand, they kind of admire me. The great desire of Mittel Europa, with Germany, with Austria, with Hungary, is: “Ya, this is a very good play, but is it world-class? Will it be treated with respect?” It means that one of us is as good as the best of them. That they admire. They admired Marlene Dietrich because she was the only female German film star that made it in this country. So it’s [a matter of] being honored—and I don’t want that—or being hated. That was Marlene’s thing, on a much higher level. You know that she never wanted to go back to Germany, and I still think that she did not ask to be buried in Berlin.

I’m curious about your period in Berlin. You and your circle of friends didn’t take Hitler very seriously until very late…

Nobody did. The situation was that in 1932 there was an election, and the National Socialists, the Nazi party, had lost about 35 percent. We just thought: Well now, they finally saw through that man, they finally grasped the basic idea of Nazism, and they didn’t want to learn it. But what happened was one of the little caprices of mother history. The Allies got Lenin and Trotsky and put them in a railroad car and sent them to Russia, so this one front they took care of. But the son of Hindenberg was involved in some kind of monetary scandal, and in order to [douse] that fire, Hindenberg demoted the liberal chancellor, General Schleicher, and appointed Mr. Hitler out of nowhere. Mr. Von Hindenberg was slightly gaga at that time—he was promised the constitution would stay the way it was and you could vote for different parties. But to grab all the power, Mr. Hitler got hold of a young Dutchman who was slightly out of his mind, locked him up in the Reichstag and started the fire there. And Mr. Hitler said, “You see what the Communists have done? There will be no other parties, only the National Socialist Party.” All of that came very suddenly, and very ruthlessly.

I was sitting in a coffeehouse with friends—Hitler came to power on January 30, 1933, and this was like in March or early spring—and we were saying, “Where can we go? What can we do?” And I saw eight or ten SS men in uniform beating an old Jew to death. I make a move, and they held me back, saying, “They’re going to kill you as well, you can’t help that.” But I knew: This is the way it’s gonna go, and I’m not going to be here.

You came to Berlin in 1926. During those first six years there, did you encounter much discrimination yourself?

Yeah, wherever there were Nazis, it naturally existed. Sure, sure, but nothing compared to what happened. The great difference is… There are anti-Semites all around the world, some of them in very high positions. But no country made it legal, and even obligatory, to kill the Jews. I mean, if you kill a Jew in Alabama, the populace is outraged: Where was the law? What happened? It’s a whole different story. In Russia, in Poland, anti-Semitism is rampant. But now, by this time, in Germany there are so few Jews they are importing them to have somebody to eat. I know the decent ones, I know the indecent ones, I know the ones who stood outraged, but within themselves there was a little jubilation: one Jew less. But then again, I don’t think the world behaved very good after it became public knowledge that they had concentration camps. I think it could have done more. I could have maybe saved my mother, but I didn’t dare because there would be one more. My father died in Berlin in ’28—he didn’t see it. But everything is being blamed on the Jews, times are bad in Germany now, it’s the Jews again. It’s absolutely incredible, and I think it cannot be weeded out—it’s been going on for all these thousands of years. And I don’t think that this thing is going to work out, this summit meeting of Rabin and Arafat. They were shaking hands, but they were also shaking hands when Sadat made peace with Begin. I think Arafat is going to be assassinated. I think we are very lucky in this country, but even so they do their writing on the walls, their graffiti, and knock down gravestones.

You wrote a film in 1940 which was one of the few to call for America to intervene in Europe, Arise, My Love. Did you meet resistance from the studio about writing a film with that kind of interventionist message?

We got many letters. What made it kind of a ticklish situation—I don’t know how many letters came to the studio saying how dare you?—was that the war was not on yet. That was before Pearl Harbor. Oh sure, there were here and there graffiti and a stink bomb thrown. That was a good picture; if it was not, Paramount would have taken back all the copies so as not to offend the German-American audience. We poked some fun: The guy at the beginning who’s in jail, his best friend was a rat, and the name of the rat was Adolf.

We should talk a bit about Sunset Blvd. Would it be wrong for me to assume there’s a lot of you in Joe Gillis?

Well, I was never mistaken for an undertaker, taken in by a lady who’s got oil gushing. Look, any writer, if he writes about even characters that don’t correspond with him but characters that remind him of somebody he knew, we draw, willingly or subconsciously, on things we have seen and lived through. Just because he was a writer—I was a writer at the very beginning, I had leather patches on my elbows not because it was chic but because there were holes in them. I submitted God knows how many scripts or synopses and was turned down, sure. But it was not quite as difficult as it is now. At Paramount, for instance, where I spent 18 years, they had 104 writers under contract. It was on the fourth floor, the writers’ annex annex, every Thursday I was to deliver 11 pages written on yellow paper. Everybody was working—not all the scripts were made, naturally—but they made like 50 pictures a year. Now you make a picture with a studio, and even if it’s a very inexpensive picture, namely $30 million, they’re looking over your shoulder, they’re kibbitzing, they’re afraid, they make you feel that if this picture’s not a hit, the studio must be sold, and the policemen will be fired and the secretaries will starve to death. They don’t leave you alone.

Back then, we decided this is the kind of picture we want to make and those are the actors we’d like to have, and then you went off and started writing the screenplay. The first thing [the executives] saw were the rushes, still not comprehending fully what those little holes on the side of the celluloid were for. Still, they sometimes had a desire to put their foot down, to show who is running this goddamn studio. They would come with suggestions for titles. They would run the rushes, as I witnessed one time: The guy who was running MGM, we came for dinner, and they were running the rushes in the living room. And there was the head of the studio and his wife and there were three kids picking their noses, 12, 14, 15 years old, saying, “Oh, that’s a lousy leading man.” You are exposed to those things. But in any case, there was not all of this tension. I think that if Jurassic Park had turned out a failure, the whole of the United States would be shaking—it would be a catastrophe of the first order. And now, we can see that we’re doing very well, because the picture’s going to make one billion dollars all around the world.

They don’t like us very much in Washington, because over the years they’ve cultivated the wrong image. In one interview with The New York Times years ago, I said, “I know what Washington has against Hollywood—that it is the only industry that is triumphant around the world, exported all around the world. If there are a hundred people waiting outside to see a French picture in Paris, there are 2,000 standing around three blocks to see an American picture. Every other industry is a loser, but American films make America’s glory and fame. And Washington thinks we’re making $20,000 a week and don’t pay taxes, that we have three casting couches in every office.” And I said, “Listen to a man who lives here. It’s all true! Now eat your heart out.”

All these inventions. People are working harder here than anyplace else. You get up at five in the morning. They are dedicated, they are professionals to a degree that no other country can duplicate.

I just picked up the history of the Chateau Marmont [the famed hotel where Wilder shared a room with Peter Lorre soon after his arrival in Hollywood].

That anecdote of Miss Little, who was running the hotel. I went to Europe, the last time I went to see my mother, I think it was in 1936. I’d made some money—I sold some stories or something. And I came back on the 23rd of December to have Christmas with some friends of mine, and I forgot to notify Miss Little. The hotel was absolutely booked up. I had my belongings there in the cellar or wherever it was. I found out that there was a ladies’ toilet giving onto the lobby, with a swinging door, not even a lock. There was a little anteroom with a couch, and then there were like six toilets. So I said, “I’ll stay here until—when are you going to have room?” And she said, “After the 26th or 27th.” So I stayed in the ladies’ room, which got very embarrassing. People would come in, look, and say there’s a man asleep there. It’s the only time I had a bedroom with six toilets.

Getting back to Sunset Blvd., are you pleased now that William Holden wound up taking the role of Joe Gillis rather than Montgomery Clift?

Oh yeah. I was full of anxiety. I had seen only one picture that he had made at Columbia. He had a contract with Goldwyn Studios alternately, and he had done Golden Boy. I saw that and I liked it. I liked his performance [in Sunset Blvd.] enormously. It was simple, and he looked like [a writer], he wore the suits like it, he talked like it. It was one of those pictures that started falling into place, it started making sense. After one weekend, we knew we had something.

We only won one Academy Award, for Best Original Screenplay. We were competing against All About Eve. Swanson didn’t get it, Holden didn’t get it, the director didn’t get it, but it is one of those pictures that gets better with time, and I think that people remember it better than All About Eve—a very good picture, and a very wonderful talent. It’s a big shame that he kicked the bucket, Joe Mankiewicz. A very, very fine picture.

Talking about originality—in those days, this was a highly original picture. It is very difficult to do it now. After they made Home Alone, there are gonna be ten more, and the kid is gonna get $40 million and ultimately marry Schwarzenegger and it’s gonna be the biggest picture. But, but—I don’t want to imply that Schwarzenegger is a homosexual, I was talking about salary.

To sum it all up, we had more fun then. We had, disposed over this here area, fiefdoms. There was the castle of Louis B. Mayer, there was Warner Bros., Paramount was there on Melrose. We did not meet. We had families. I remember one day I was having dinner with the wife of Bill Goetz, the daughter of Louis B. Mayer. And I told her come Monday I’ve got to go to Berlin to do a picture called One, Two, Three. “Who is in it?” she asked. I said, “Jimmy Cagney.” And she said, “Who? I don’t know him.” And I said, “What do you mean you don’t know him?” [I explained who he was] and she told me, “My father absolutely forbade us to look at any Warner Bros. pictures, because they were all about gangsters and about the ugly side of human behavior.” She did not know him.

If I had a script, let’s say, for Gene Kelly—as a matter of fact, I did. I went to the people at MGM, and they absolutely thought I was mad! “You think we’re going to give you Gene Kelly?” This was like asking if you could take the Virgin Mary to Romanoff’s restaurant. The idea was so absurd. They only let Mr. Gable go to Columbia for that one picture for Capra, It Happened One Night, because he was in three failures, and they thought: Capra is a hit director, maybe he can bring him back for us.

Garbo, I remember, I talked to her. She came up to the house for a drink, and I said, “Are you or aren’t you going to make another picture?” And she said, “I will make a picture, but only if I can play a clown!” I said, “Why would you want to play a clown?” “Because I don’t want to show my face, I would have a mask…” “You mean not even at the end?” “No, no….so, you have a story with a clown?” I said, “Not at the moment.”

While you were at Paramount, you were loaned out to MGM…

For Ninotchka. But then we were loaned to Mr. Goldwyn, who had Mr. Gary Cooper under contract. Paramount got him for that Hemingway thing with Ingrid Bergman, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and in exchange they got Brackett and me to write a picture [Howard Hawks’ Ball of Fire] and they got Bob Hope for a musical, The Goldwyn Girls or something. Gives you the idea of the value of people: “I’ll give you Bob Hope, plus the writing team, whatever their name is, and you give us Gary Cooper, and you’ve got a deal!”

This is what happened to me, in a sense, on a rainy evening outside the Spago restaurant: There are always autograph hounds, with the autograph book and the camera and the fountain pen that does not write. One rainy night, there were very few people, and one of them came up to me and said, “Mr. Wilder, I would like an autograph. As a matter of fact, I’d like three of your autographs.” “Why three?” He says, “Because for three Wilders I can get one Spielberg.”

I haven’t read much of you talking about Howard Hawks.

Howard Hawks? After the script for Ball of Fire was finished. I took kind of a leave of absence for two months and stayed behind, somewhere up the ladder, watching how Hawks went about it, how he connected scenes—he was a very fine technician, you know—how he made every scene have three acts. The thing I learned from Hawks is: Make it simple… I learned that crazy, absurd, unheard-of camera setups are not going to make a director. It’s going to remind the audience that there was a big crew that was tilting the camera. There’s a whole group of directors that photographs a living room through the fire in the fireplace. And I’ve said, “That is from whose point of view?” Maybe Santa Claus, I don’t know. I’ve learned how to shoot elegantly, so that the seams don’t show. And I always shoot very fast—I’ll shoot in one day instead of two, with the understanding that should I, after seeing it in the rushes, think that I require more shooting, I’m going back and doing it. But I don’t do it to be covered, a priori. No, I just shoot the way I think it’s going to look. And when I’m finished with a picture, there’s very little celluloid left on the cutting-room floor. I’m using everything. People cover themselves: First comes the long shot of everyone sitting around the table, then there comes a medium shot, then over this shoulder, over that shoulder, then a close-up of the same thing, and the actors have to repeat the same words for all those angles, 30 times. No, I just…more or less, I overlap one or two speeches, but I know the way it’s going to go and I hope that it’s going to work.

And a big part of that way of working was [Wilder’s longtime editor] Doane Harrison…

Doane Harrison, naturally, was one of the great influences of my life. I went to the Doane Harrison College, and I miss him very much. Doane Harrison was kind of old Hollywood—he was the cutter for Hal Roach when George Stevens was the cameraman.

I know one of your personal favorite films is Ace in the Hole, which must seem timelier than ever now with all these awful tabloid TV shows.

Yes, well, unfortunately, it did not make any money. Then, behind my back, because I was making a picture in Paris at the time, Mr. Freeman, head of the studio—his name was Y. Frank Freeman, and the joke was: “Y. Frank Freeman? A question nobody can answer”—he changed the title from Ace in the Hole to The Big Carnival, like this is going to attract people…without asking me! That was one of the reasons I left Paramount. Head of a studio—if you can’t write, you can’t read, you can’t act, you can’t compose, if you can’t do anything of that sort, you become the head of the whole thing.

Is there anything about that film you might have done differently, in light of its box-office failure?

No. I think it came out pretty good. A lot of people are bringing it up. Financially it was a failure, but not totally a failure, because many, many people are talking about this particular picture.

You still got an Oscar nomination for it.

I did? For what?

For Best Original Screenplay.

See? The intelligent writers.

Here’s a general question. So many of your characters are scoundrels. Why is that? Is it just because they’re more interesting dramatically?

You’re very close. The proper answer to that is: Virtue is not photogenic. A man leaving his apartment opens a drawer and takes out a handkerchief and puts it in his pocket and exits. But if he opens the drawer and takes out a gun and puts in his pocket, you’ve got a scene. I love to have situations where people are entering rooms through windows, not through doors. It carries suspense, it carries some kind of excitement, and also it is easier to act. You know, the most difficult line for an actor is to open the door and say: “Tennis, anyone?” That’s a deadly line. But to come to the door and say, “I just got the call. This is the moment. Don’t forget the submachine gun.” You know what I mean, you’re in a situation. But “Tennis, anyone?”—how can you, even if you’re Cary Grant? “Tennis anyone?” would only be a good line if somebody comes in in a wheelchair.

Speaking of Cary Grant, I have to believe Sabrina is a much different movie with Humphrey Bogart as the lead character than Cary Grant. Are you happy with the way that character turned out in the film?

In a way, yes, of course. There are quite a few cases of Cary Grant, who was a friend of mine… Lubitsch wanted him for Ninotchka, I wanted him for Sabrina and Love in the Afternoon. I don’t know, for some reason or another—maybe he thought I was a Nazi. I never made a picture with him, and I really liked him enormously. I liked what he did, which seems to be so easy. It’s a very difficult thing to be a leading man in a comedy.

I wasn’t telling him that I wanted him to act a murderer or some depraved thing, the Hunchback of Notre Dame. The part that he was absolutely ideal for [was in Ninotchka]—it’s very sad that we did not see Garbo with the best of the light comedians. It was just not to be. And I can’t have him back now.

But the idea of having Bogart I kind of liked, because it’s against the grain. Nobody suspected that he was going to wind up with Audrey Hepburn. Making a deal for his brother to marry the daughter of a rich, complex-owning family—he manipulates that, but then he himself falls into the trap. It’s not the common thing, that Bogart wins over the more attractive Holden—except maybe for one reason, that he got the bigger salary. That’s why he got the girl.

Could you talk a little about your breakup with Charles Brackett? My theory is that your areas of interest were diverging too much.

It’s like a box of matches, collaboration. You take out a match and you strike it and you light your cigarette. But if you do that often enough, the surface on which you strike it…it does not catch anymore—it is all used up… It was a series of—never, never screaming fights, we still remained friends—but I thought I maybe needed another striking surface. But in all that time, I had only one other collaborator, Raymond Chandler. It [Double Indemnity] was a little too grisly for him.

We had many arguments. The argument that sort of broke it off was we had the ending of Sunset Boulevard blocked out, we knew this man who wanted a swimming pool got a swimming pool, died in a swimming pool. We knew that she is going to shoot him. The script was not yet finalized; the last ten minutes—we had it, but it needed work. He was working on it and came to me and said he found the solution as to how this woman who is suicidal, and everybody is very careful about having no locks in the doors and no razors around, how she has a gun to shoot him. Brackett and [co-writer D.M.] Marshman came up with this very complex thing—that she got the gun from the old doorman at Paramount who recognized her. I said, “Charles, this is too long, this is not gonna work.” And he said, “Well, how are you gonna do it?!” I said, “She says to him, ‘I got myself a gun,’ and she lifts the pillow and there’s a gun there. How she got it, nobody knows. I don’t give a shit… I’m not going to go into side plots. I said, “Look, if it is a plot point and it gets too complicated, we can’t use it. Let’s just throw it away. She says, ’I got myself a gun.’” That was one of the [arguments]. But I would not have that with Diamond, for the very simple reason that Diamond was, in the words of my beloved wife, “the world’s greatest collaborator, with the possible exception of…” [Wilder is stuck for the name] …the Norwegian who was collaborating with the Germans, who was shot. A lot of stories about him. [Wilder can’t come up with the name Quisling, and I’ve just failed European history. He’s upset that he can’t remember it.] You should never start a joke unless you rehearse it.

A lot of your films center on American businessmen. What is your fascination with them?

I never thought of that. Whereas other pictures are…what?

Well, there’s Love in the Afternoon, The Apartment, Avanti!…

But I can tell you many other pictures—pictures about journalism, pictures about insurance agents. I don’t know. We have over 120 million men in this country, of which 90 or 100 million are businessmen. It’s not such a—if you told me, isn’t it amazing that in 90 percent of your pictures, the male lead is an astronomer? They are businessmen, but at least they are in different businesses.

Let me find a better question then. You’ve often proclaimed your love of America and your desire to come to America when you were back in Germany. At what point did you feel comfortable with criticizing American society?

Immediately. But the pluses outweighed so much the minuses. I was not a blind, idiotic patriot, you know. I came to America because I loved Roosevelt. In any case, Hitler or no Hitler, I would have ultimately wound up in America, as every picture-maker in Europe dreams he is going to do. ‘Cause this is the capital—they make good pictures in France and England, but if this is your profession, you would like to live here. But I was a critic of Roosevelt, too—there was that thing with the ship with all the refugees and he decided to send them back, and it took the German captain to run the ship ashore in Scotland because he knew that they would go to Dachau.

Did the country seem more puritanical than you thought it would be when you got here?

The world was more puritanical. You go to London or Paris or Berlin, they have changed, too, and not for the better. It is not that it is a typical American revolution of our mores, of behavior—the criminality, whatever you want to call it. They are right there with us—in Austria, in Berlin, in London. I dream of it the way it was in 1930, but, especially now with the fax and the rapid method of traveling, the mystique of America, or of Europe for the Americans, has evaporated. There’s almost nobody that I know that has not been in Europe—they know the hotels, they know the restaurants, they copy the Americans, the Americans copy the Japanese, blah, blah, blah. It’s become one, flattened-out globe where people are living almost the same way. It’s not that big a contrast. When I met somebody from America when I was a newspaperman, it was a tremendous event for me, even if he was pretty stupid: “This man, this man, is an American!”

As I told you, Mr. Lally, if you are uncertain of facts, do call me. In any case, it’s good that you met me, because I may be a little less bellicose, or whatever you want to call it, than people have made me out.

Is there anything in the Maurice Zolotow book [the first Wilder biography, published in 1977] that you want to correct for the record?

Yes, there a lot of things. For some reason, he wanted to find the theme, the Wilder theme.

He wanted your “rosebud.”

And he came up with the most grammar-school version of a Freudian explanation. In my youth, so he says, I fell in love with a girl and then found out that she was a prostitute. Therefore, I hate women… I knew the girl to be a hooker. She was very pretty, and I paid her. There were hookers in my life, but I was never in love with a hooker.

However, he has one thing that is so stupid. I was ghostwriting for a guy called Franz Schultz—he called himself here Francis Spencer, so as not to have to change the initials on his shirts. I remember one day in Berlin I came to work and his eyes were black and blue. “What happened?” I asked. He said he was having an affair with Mrs. Erich Maria Remarque, and Erich beat him up. I did not tell this story, I don’t know where Zolotow got it from, but suddenly it says that I had a long affair with Mrs. Remarque. I had never seen her in my life! I knew Remarque himself because we worked for the same publishing house, before All Quiet on the Western Front. But there are mistakes there…flatitudes instead of platitudes. But that’s all right—the guy had a terrible life, he spent half his life with Alcoholics Anonymous. He was a sweet man. But don’t write what is not true. I’ve never been connected with any gossip thing… I don’t give information like this, I don’t talk about it in interviews. Maybe a leading man needs some of that kind of publicity, but not the guy who’s writing and directing. It’s shabby, very shabby to do that.

Well, you’ve been with your wife since 1949. That’s a pretty remarkable union.

Ya, we got married in Nevada, and Mr. and Mrs. Charles Eames were my best man and the matron of honor.

So you will remember that I am here, and I’d much rather that you call me than speculate, and I will tell you the truth. I know what makes for good reading, but, on the other hand, what makes for believable reading? [The interview seems to be ending, then begins again.]

Once you engage in the making of a movie, and you know after the third day this is not going to work, you still have to finish it. They’re not going to put it on the shelf to collect dust, they’re going to show that thing. We don’t bury our dead. We try to squeeze out the last penny, even if it is way below the standard of the picture-maker, by some miscalculation. It is just wonderful with a play—the plays that never reach New York, by Kaufman and Hart and very successful playwrights. But not with a movie—maybe once every 20 years, something is so bad that somebody very clever takes the negative in the night and buries it. It’s very, very difficult when a film looks like it’s going to live, like it’s going to breathe, and suddenly it just doesn’t have—not everything has to have magic, but some allure, something. Show me a director who never has a failure, and I’ll show you a man who always has done cowardly pictures… A cowardly man just makes pictures that have been made before, and he gets away with it. He’s not going to get great reviews, it’s barely going to make its money, but, by God, he never had a total failure. Only the man who dares to try a picture which may turn out to be a total disaster, or a total success, that’s the man that I like.

Even your failures are very interesting…

I’ve had many a sleepless night… If you collapse in the middle of the picture, just try to make the best [film] you can make. It’s torture…but you still go and finish it.

I’ve always felt that you were much too hard on Kiss, Me Stupid. I know it’s a bad memory for you, but I think mainly you were just a victim of the times. If it had come out a few years later, it might have been much better received.

Instead of analyzing and rethinking after the failure, I don’t spend too much time on it. I’m already preparing another failure. Hopefully not. All that chest-beating is just a waste of time, it’s self-torture.

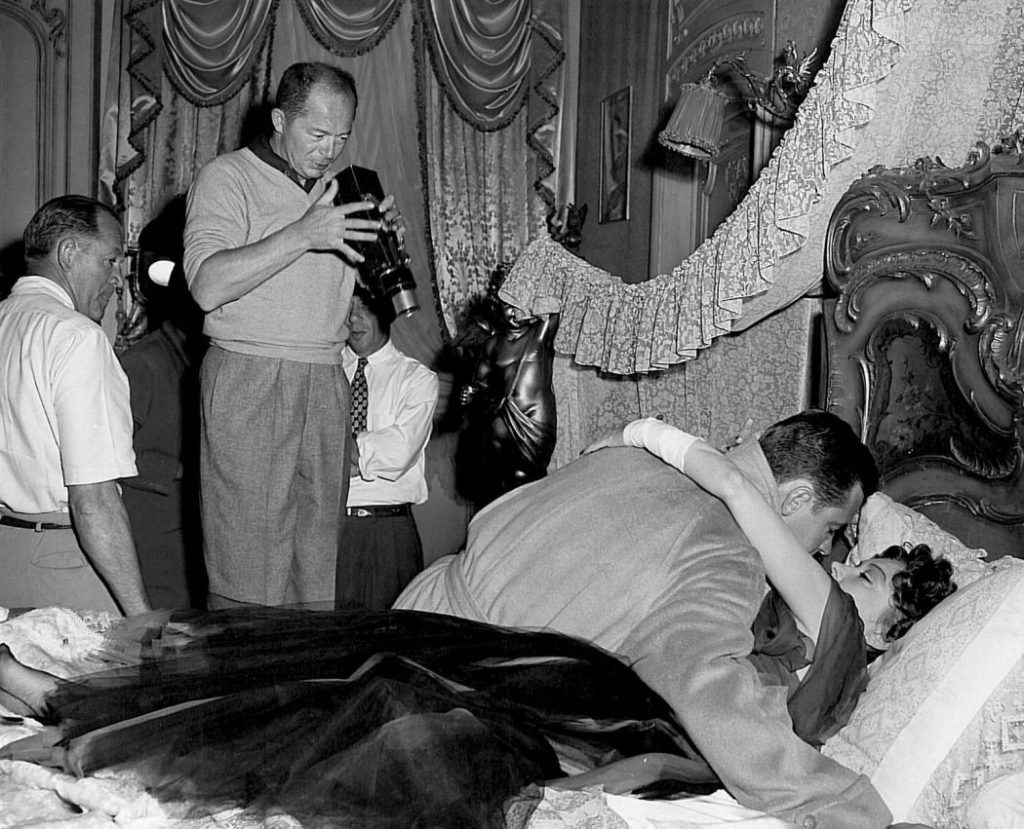

Pictured: Billy Wilder directing William Holden and Gloria Swanson in Sunset Blvd. Much more to come in future months.

Leave a reply to Billy Wilder’s Battle With the Past – toptrends.io Cancel reply