Four-time Academy Award winner Nick Park is back in the Oscar race with Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl, the latest delightful adventure featuring his irresistible stop-motion creations, eccentric inventor Wallace and his melancholy dog Gromit. Co-directed by Park and Merlin Crossingham, this Netflix release is the animated duo’s first screen appearance since the 2008 short A Matter of Loaf and Death.

This year also marks the 25th anniversary of one of Park’s biggest successes, Chicken Run, the first feature from his home studio, Aardman Animations. (A sequel, Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget, was a BAFTA nominee last year.) With Aardman back in the news, it seemed like a good time to revisit my 2000 interview with Park and Aardman co-founder Peter Lord, discussing the challenges and rewards of their stop-motion artistry.

The people at Aardman Animations, Britain’s leading animation house, have been in a “fowl” mood lately, as they race—one frame at a time—to meet the June 23 opening date for Chicken Run, their first full-length feature, part of a $250 million, four-picture deal with DreamWorks. Co-directors Peter Lord and Nick Park may be up to their necks in clay chickens, but that hasn’t diminished their excitement over this landmark achievement for the 28-year-old company. “I think a new page has been turned at Aardman,” says the Oscar winning Park, “in that we’ve created a world that’s so much bigger and more believable than anything we’ve done before.”

What is Chicken Run, exactly? Think Steve McQueen in The Great Escape, but in the guise of a rooster, gunning his motorcycle to avoid being turned into a McNugget. “Pete and I came up with this very simple idea—an escape movie with chickens,” Park explains. “It was just that combination, that joke—we laughed and we thought: You can go somewhere with that. We love referring to movies, and this is perfect for that—there are so many prison movies and escape movies to refer to.”

Based in Bristol, England, Aardman has been a major force in the field of stop-motion animation (also known as model animation) for nearly three decades. Co-founders Lord and David Sproxton first gained world acclaim with their witty series called Conversation Pieces, in which clay figures performed to real-life dialogue recordings. MTV viewers will surely remember Peter Gabriel’s wildly imaginative “Sledgehammer” music video, which Aardman did in collaboration with Stephen Johnson and the Brothers Quay. The company won its first Oscar with Park’s Creature Comforts (1990), a hilarious short airing the gripes of various animals in a zoo. That same year marked the debut of Park’s classic creation Wallace and Gromit, a cheese-loving inventor and his long-suffering dog, in the Oscar-nominated short A Grand Day Out, which Park began back in 1975 while attending the National Film and Television School. This internationally beloved pair subsequently starred in two Oscar-winning shorts, The Wrong Trousers (1993) and A Close Shave (1995).

Lord admits that the transition to feature filmmaking has been daunting. “It’s very difficult just to keep the story going, to keep the energy level up, and the sheer scale of the production has been really challenging. If you compare Chicken Run to, say, A Close Shave, although it’s two and a half times as long, it’s twenty times as much work.

“Technically, the chickens are quite different inside, as it were, under the skin,” Lord notes. “They were built in quite a different way, just for practical purposes. Chickens are very, very difficult to animate, very difficult shapes to work with. When you think about it, they’re great big round balls of feathers on two little thin legs, with little heads perched on top. You certainly couldn’t work in just solid clay the way we used to. We worked really hard to make them work, and we also worked really hard to make sure, as a viewer, you’re not aware of how they’re made. They look pretty much like clay, but there has been a major advance in the way we make films.”

Lord and Park have been colleagues since Park joined Aardman in 1985, but this is the first time they’ve co-directed a project. “We knew that one person couldn’t do a movie on this scale alone,” says Park. “The amount of plates to keep spinning at once was just too difficult.”

Asked how he developed the patience to work at a craft where a full day’s work yields just a few seconds of film, Park insists, “It’s more endurance than anything else. You don’t have time to be patient. A lot of people think you need patience, but it’s more those who are waiting for decisions to be made. That was the good thing about having two of us—thirty cameras were rolling on thirty sets every day, and we needed to get round to fifteen sets each day, to talk to the respective animators and set builders and camera-lighting people. And they all want decisions.”

Lord speaks admiringly of the many craftspeople who have contributed to the world of Chicken Run. “We’re asking so much from so many people, apart from ourselves. We’re asking them to keep coming up with good performances every day for eighteen months, to keep inspired and creative. And I do think that keeping everyone going is part of the art of it. Neither Nick nor I are the sort of directors who shout at people and terrify them into action. We just aren’t that kind of person. An awful lot of the work is motivational, finding the right word for the animator, the right keyword that sets them in the right direction.”

In a period when computer technology has opened many new possibilities, Lord and Park still prefer the hands-on experience of model animation. “The very material, the very fact that it’s tactile, is important,” Lord insists. “I think the audience are aware of it. We try to animate smoothly, we don’t want the audience to be distracted by the idea that they’re watching animated clay, but we don’t try to disguise it either, because we believe that things that are handmade and handcrafted have more humanity in them than things which are mass-produced. And I think that humanity comes through. That’s because animating with plasticine is a very physical, distinctive process—you’ve got this stuff in your hands, on your fingertips, and the very slightest touch in pressure, especially around the face, changes the expression. Very gentle, subtle, and instinctive touches bring the characters to life.”

Adds Park, “You can be cartoony because you can almost draw with your modeling, but you’re also dealing with something close to live action, too. You can light it and you can shoot it from different angles and you can play around with the camera and get some nice angles. It’s like being on a movie set with a miniature.”

“It’s actually quite like a live performance, because you get one go at it,” Lord notes. “With drawn animation or computer-generated animation, a shot is built up and assembled and refined possibly over weeks, possibly over months even, and when the elements come together it’s very beautiful and very smooth and very perfect. Whereas with us, a shot starts at the beginning and runs through to the end and it’s done in a number of hours—it may be thirty hours, it may be five hours, but whatever it is you can’t change things, you can’t go back and correct it. And that means it’s not perfect, but it’s also more alive.”

“The whole process is very vulnerable,” Park says. “A six-second shot can take two or three days, and anything can go wrong in that time, especially overnight. We’ve even had mice come in and eat half of the set. Usually, the most common problems are that the set would warp with a change of heat, or things like leaves coming into the room, so I do admit that we have relied on a bit of CGI just to correct things like that.”

Anyone who’s seen behind-the-scenes footage of Lord and Park at work will be amazed by how small their big-screen creations really are. Park explains, “What you need is a size that’s just enough to manipulate and not too much work, but also not so small that you keep getting nail marks in it or fingerprints too big. But we don’t mind fingerprints. We love fingerprints. I think that’s kind of endearing to people, that when they see fingerprints they can relate to it, because everybody’s played with clay or Play-Dough or plasticine.”

“We try to operate a very particular balancing act,” Lord says. “When the audience watches the film, we want them to be totally involved, we want them to believe the characters are alive, care what happens to them, believe their emotions, be excited, all those things. But at the same time, we know that part of their minds is also saying, ‘That’s clay, that’s a clay model and I could pick it up. If I were there, I could lift it up off the set. It’s real.’ When those two things work together—the awareness of how it’s done and at the same time a complete absorption in the story—then that’s great.”

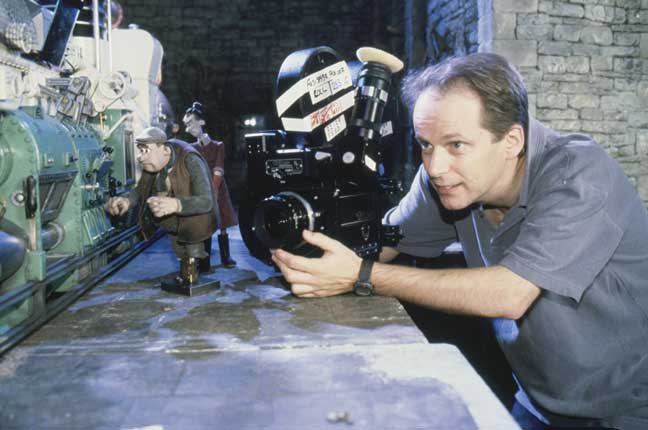

Pictured at top: Nick Park in production on 2000’s Chicken Run.

Leave a comment