The 62nd New York Film Festival ends on October 14, having screened 73 features plus various programs of shorts. I managed to see 28 films over a whirlwind three weeks of press screenings. Here are some highlights, in addition to the films I’ve discussed in previous posts.

One of the most haunting and disturbing films at the fest was I’m Still Here, the new drama from Brazilian director Walter Salles (Central Station, The Motorcycle Diaries, On the Road). It’s the true story of the Paiva family, who lived through a nightmare scenario in Rio in the early 1970s. Rubens Paiva (Selton Mello) is a former congressman who heads a lively, upper-class household including four daughters and a young son with his wife Eunice (the compelling Fernanda Torres). One day, military goons arrive to whisk away Rubens for a “deposition”—he’s never seen again. Later on, Eunice and her teenage daughter Eliana are taken for an interrogation; Eliana is released, but her mother is detained for 12 days under terrifying conditions. Eunice persists in seeking the truth about her husband’s disappearance while keeping a brave face for her family. Ultimately, she earned a law degree at age 48 and became a notable activist. Eunice also learned that her husband played a covert role in the resistance and was murdered while in captivity.

For the first 30 minutes of the film, Salles and screenwriters Murilo Hauser and Heitor Lorega portray the warm, raucous bond of this loving family—the one piece of ominous foreboding occurs when oldest daughter Vera and her friends are stopped at a roadblock and interrogated at gunpoint. The Paiva family is so relatable, it comes as a stunning blow when their lives are so cruelly turned upside down. Sony Pictures Classics will release I’m Still Here early next year—it’s a must-see.

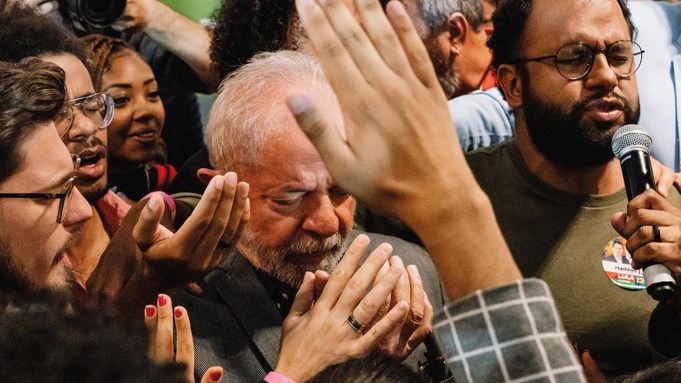

As we know, the political situation in Brazil has once again regressed. Petra Costa’s documentary Apocalypse in the Tropics reveals how much of the current tumult in that nation is directly linked to the influence of Christian evangelicals, both Brazilian and American. The roots of this go back decades to preachers like Billy Graham, who were aligned with conservative American politicians in their opposition to the Catholic Church’s liberation-theology wing. Today, the leading champion of the evangelical movement in Brazil is popular TV preacher Silas Malafaia, a mentor to the country’s dictatorial former president, Jair Bolsonaro.

Apocalypse in the Tropics

Costa obtained remarkable access to both Malafaia and Bolsonaro, despite her own opposition stance, as well as Bolsonaro’s socialist opponent Luiz Ignacio Lula de Silva, who returned to power in an extremely close election that led to riots eerily echoing America’s January 6 insurrection. That’s not the only echo of what’s happening in America, where the bedrock separation of church and state is being challenged in many quarters. Costa, by the way, is not only a shrewd historian but a true filmmaker—the look of the movie, with its many aerial drone shots, is exceptionally handsome.

TWST: Things We Said Today

Bear with me as I try to explain Romanian filmmaker Andrei Ujică’s experimental documentary TWST: Things We Said Today. Assembled from many hours of 8mm home movies and 16mm news footage, this portrait of mid-August 1965 centers on The Beatles’ trip to New York to perform at Shea Stadium but branches off into several other tangents. There’s footage of the Fab Four’s arrival at JFK Airport, the throngs of teenage girls wreaking havoc outside the Warwick Hotel, and the press conference in which the group fields insipid and decidedly un-hip queries. In counterpoint to the chaos surrounding The Beatles are scenes of the scarier riots happening across the country, in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. As first-person source material, Ujică uses narration taken from the journals of writer Geoffrey O’Brien, the then-teenage son of WMCA DJ Joe O’Brien, whose station was an early Beatles booster, and Beatles fan and concertgoer Judith Kristen. The two are represented by crude drawings superimposed over the archival footage to give a “You are there” sensation. Ujică also incorporates excerpts from an unrelated short story he wrote, which is one layer too many for me.

The film also includes an extended visit to the New York’s World Fair adjoining Shea Stadium, a blast from the past for this senior, who visited the fair seven times as a pre-adolescent. Beatles fans will be crushed to hear that the doc includes no moments from the Shea Stadium concert—indeed no Beatles music, including the title song. But the footage here remains hypnotic, a true time-travel experience.

Marianne Jean-Baptiste in Hard Truths

I’m a longtime fan of British writer-director Mike Leigh, but his latest film, the aptly titled Hard Truths, left me unsettled. Marianne Jean-Baptiste, an Oscar nominee for his 1996 drama Secrets & Lies, stars as Pansy Deacon, a woman so argumentative and disagreeable, she makes Larry David look like Mister Rogers. For the first half of the film, her confrontations—with a furniture store saleswoman, on the supermarket checkout line, with her doctor and her dentist—are so outrageous, you can’t help laughing. Then Leigh pulls the rug out from under you: Why are you laughing? This woman is in psychic pain, physical pain—she’s simply miserable and can’t help lashing out.

In stark contrast is her sister, Chantelle (Michele Austin), a hairdresser who radiates warmth and shows remarkable patience with her ornery sibling. A Mother’s Day gathering—including Pansy’s put-upon husband Curtley (David Webber), her obese and socially awkward grown son Moses (Tuwaine Barrett), and Chantelle’s vivacious daughters Aleisha (Sophia Brown) and Kayla (Ani Nelson)—is painfully uncomfortable, but it seems to be a possible emotional breakthrough. Perhaps. The film is frustratingly open-ended, but maybe that’s the right call. A problem like Pansy isn’t about to be solved overnight. Kudos to Jean-Baptiste for her volcanic, no-holds-barred performance.

Brandon Wilson and Ethan Herisse in Nickel Boys

The festival opened with Nickel Boys, documentarian RaMell Ross’s adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, inspired by a real-life Florida reform school that brutalized—and sometimes murdered—its students. The central character is Elwood (Ethan Herisse), a gentle Black teen who is headed for technical college when he makes the mistake of accepting a ride from an older man who’s stolen a car and is caught by the police. Elwood is sent to Nickel Academy, a rigid institution which has a brutal take on the concept of reform. There, Elwood forges a friendship with the much more cynical Turner (Brandon Wilson).

Ross has made a bold stylistic choice here, filming everything from Elwood’s subjective point-of-view, then alternating with Turner’s once the boys meet. The device produces some beautiful imagery (shot by DP Jomo Fray) and is likely intended to avoid dwelling on the sadism-porn aspects of the reform-school environment. But paradoxically, this invitation to live inside the skins of the main characters creates an emotional distance that a more conventional approach might have dodged. This impressionistic film certainly has its poignant and powerful moments, but Nickel Boys feels like a missed opportunity.

Saoirse Ronan and Elliott Heffernan in Blitz

The festival’s closing-night film, Blitz, is among its most ambitious. Writer-director Steve McQueen has crafted a harrowing, monumental recreation of London in the year 1940, when the city was the unrelenting target of German bombers. At the center of the story is factory worker Rita (Saoirse Ronan), who makes the wrenching decision to put her half-Black son George (Elliott Heffernan) on a train to the relative safety of the countryside. But George never wanted to go, and he jumps from the train and makes a pilgrimage back home. That’s the beginning of a Candide-like series of adventures that have him crossing paths with three runaway brothers, a kindly Black air-raid warden, and a den of nasty thieves out of Dickens.

McQueen, whose 12 Years a Slave didn’t shy from the sadistic side of slavery, doesn’t pull punches here either. Yes, death was all around during the blitz, but some of McQueen’s narrative shocks seem unnecessarily cruel: the sudden death of a young boy, a nightclub full of revelers who are decimated in a bombing. Photographed by Yorick Le Saux and designed by Adam Stockhausen, the production is spectacular, but almost too stylish. At the end of 12 Years of Slave, I was heaving and sobbing. Blitz, with its familiar tale of a mother-and-child reunion, left me a little cold.

Pictured above: Selton Mello and Fernanda Torres in I’m Still Here. Photos courtesy of Film at Lincoln Center.

Leave a comment