Paul Schrader made an auspicious directing debut 45 years ago with Blue Collar, a hard-hitting drama about three struggling Michigan auto workers who turn to crime. Already celebrated as the screenwriter of the landmark Taxi Driver, Schrader continued to pursue parallel tracks as writer-director (Hardcore, American Gigolo, Cat People, The Comfort of Strangers, Light Sleeper, Affliction, Auto Focus, The Walker) and in-demand screenwriter (Obsession, Raging Bull, The Mosquito Coast, The Last Temptation of Christ, Bringing Out the Dead). His two most recent films as writer-director, First Reformed (2017) and The Card Counter (2021), earned him some of the best reviews of his career (and his first-ever Oscar nomination for writing First Reformed). His latest film, Master Gardener, starring Joel Edgerton and Sigourney Weaver, opens on May 19, 2023.

I had the privilege of meeting Paul Schrader in 1985 to discuss Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, his most stylistically bold film. Here, he talks about the challenges of setting this audacious project in motion, and the wisdom of keeping plenty of pots on the stove.

“If you have enough pots on the stove, one of them will come to a boil. You have to have patience.” So advises Paul Schrader, whose provocative career as a screenwriter and writer-director has involved a lot of steadfast pot-watching. Now, after more than four years of waiting, one of his pots is suddenly boiling over: At his production office at Warner Bros. in New York, a sleepy-eyed Schrader confesses to staying up all night reworking his once-shelved screenplay Born in the USA, which his investors are expecting in less than a week.

The sudden interest comes out of the immense success of Bruce Springsteen’s album of the same name—a name Schrader says was inspired by his script. But now the filmmaker is taking the Springsteen elements out of Born in the USA. “I’d originally done it as a brother-brother story, and I felt that, now, people would regard it as a knockoff of Springsteen. So I’ve rewritten it as a brother-sister story, with the sister in the lead, which is the kind of situation Springsteen doesn’t deal with very much. So it won’t appear to be ripped from the grooves of the album. It’s one of the ongoing ironies of the film business.”

Schrader is used to dealing with such ironies, as witness the behind-the-scenes drama of his current film, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters. Under any circumstances, this biography of Yukio Mishima, Japan’s best-known novelist, is a highly unusual project—an American production filmed in Japanese by a director who doesn’t speak the language. Adding to the challenge were the delicate negotiations between the filmmakers and Mishima’s widow, Yoko, who sought to suppress any portrayal of her husband’s more scandalous aspects—his homosexuality, his obsession with violence and death, and the details of his ritual suicide in 1970 following a small-scale coup at Eastern Army headquarters in Tokyo.

As Schrader describes it, “We made a legal arrangement and have totally lived up to the terms of the contract. About a month or so before we began shooting, when it became apparent that the film was actually going to be made, [Yoko Mishima] started asking for more changes, outside the parameters of the contract. I think she had in her mind the idea that she was going to have control over the film, which she did not have legally. And I had to say no, I’m not going to change the script at this point to your liking. So then she withdrew her support and took a public position against the film before it was being made—that is her position to this day and she refuses to see the film.

“When I first approached her,” he continues, “I said I was not interested in making a film about homosexuality or about politics or about blood and guts. I said I was interested in the theme of art and action, and that’s the film I made. The agreement did not stipulate that those elements had to be excluded, it just said that they could not be central. And I had no intention of making them central—I’m not the man to make a film about the homosexual Mishima, I don’t want to make it and I shouldn’t be making it. The same with the political thing. And I certainly didn’t want to make a film exploiting his death. But what I did is in no way a compromise; If I’m going to compromise myself, I’m going to do it for a lot of money—I’m not going to spend two years working for nothing in order to compromise myself. I made the film that I set out to make.”

Mishima is clearly a labor of love for Schrader; he admits that “in order to get the film financed, I had to make deals which not only precluded me from getting a salary, but from ever seeing any money anyway.” Financing the $5.5 million film was touch-and-go from the beginning. In an interview with The New York Times, co-producer Tom Luddy of Francis Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios spoke of how Zoetrope’s financial collapse prevented it from making a $150,000 rights payment to Yoko Mishima and Mishima’s literary executor, Jun Shiragi. “We kept the deal alive,” he said, “by sending $800 and a note that said, ‘We’re a little bit short on our first payment.’” When pre-production began in Japan in November 1983, money still had not come in from the prospective Japanese distributor, Toho-Towa, and the film was sustained through hefty loans obtained by Japanese co-producer Mata Yamamoto. In December, a desperate Luddy went for help to George Lucas, whose influence brought in Warner Bros. and its $3.5 million by April 1984. By that time, Toho-Towa’s money had also come through.

What about Mishima’s life is so compelling for Schrader to persevere through constant financial hardship and wrangling with the author’s intransigent widow? “I’ve always been interested in people who are uncomfortable in their skins, or trying to get out, whether that be through some kind of religious experience or some kind of physical action,” Schrader says. “Mishima was very Western in that way, in that he was very uncomfortable in the group and Japan is the worst country in the world to be uncomfortable in the group. In the West, Sartre says hell is other people; in Japan, heaven is other people. The idea of being Japanese is to be part of the group, and Mishima wasn’t. That’s why they still don’t understand him and that’s why he still scares them. He’s very un-Japanese—I wouldn’t have dared to make another film about a Japanese author such as Tanizaki or Dazai; I could only deal with Mishima because his problems were so similar to so many Western problems.”

Schrader says that in some ways it was easier to direct a film in an unfamiliar language. “You don’t have to do a lot of hand-holding, because it’s done by intermediaries. The film is basically directed by three people—myself, my sister-in-law Chieko, and a friend of mine, Alan Poul, who’s lived in Japan for some time. We directed as a unit—Chieko was in charge of the line readings and Alan was in charge of the crew. All films are collaborative, and in this case it was just a little more collaborative. I don’t think that diminishes my ability as a filmmaker to share those functions.”

The director describes Mishima as “a totally manipulated piece of work, a contrived mosaic,” but says that arriving at the film’s complex structure was much simpler than it seems. Schrader says he and his brother Leonard (his collaborator on the screenplays of Blue Collar, The Yakuza and Old Boyfriends, and now the acclaimed screenwriter of Kiss of the Spider Woman) “went down to Mexico for four or five days with a couple of suitcases of books, and just started working it out. It’s just a series of problems, and as you solve them, it becomes apparent what to do. First, you have to get into the novels—I think that’s why there’s never been a good biography of a writer, because you can’t really see his real life. With a painter you can show his paintings, with a composer you can play his works, but a writer…what can you do? Show him typing or show his book covers? You have to actually dramatize his fantasies, you’ve got to get into his books. In Mishima’s case, you have to get into his other great theatrical production, which is his death. So you have those two elements, and then you use biographical material to tie them together. Then you have three styles: You have a kind of bleached documentary style for the last day, you have black-and-white for the past, and then I was going to do the novels in video—but after I saw the state of the art in high-definition video, I realized it just wasn’t good enough to serve the originals. So I decided to do the novels in a theatrical sense [with stylized sets designed by Eiko Ishioka}, because Mishima was essentially a man of the theater.

“Then I broke his life into a thematic progression, into four stages of his thought—beauty, art, action, and the final death. I simply laid the three-part grid over the four-part grid and saw where things fit in, which books and which events meshed.”

Schrader, whose strict Calvinist upbringing kept him from seeing any films until the age of 17, believes Mishima is “the only film of mine where the writing and the directing are equally good. I feel with this film I’ve reached a place in my own self-education about filmmaking where I can do both. I began as a writer, and in my first films as a director I was basically illustrating the scripts. And then I got very interested in visuals, and I swung over to more and more stylized films; that also comes together with this film, which is highly stylized but also, I think, well-written. It might be the end of a cycle, because Born in the USA goes back to the streets, starting again where I did with Blue Collar. It’s a realistic, gritty film that is not about the camera, but about people.”

Another Schrader-penned project that’s been long on the back burner is The Last Temptation of Christ, his adaptation of the Nikos Kazantzakis novel which Paramount Pictures canceled last year after investing $2.5 million in pre-production costs. “I think it’s the best script I’ve ever written,” Schrader says, “and it’s Marty’s [Scorsese’s] life passion to make this film. And it will be made, someday, some way, either by me or Marty. The subject certainly won’t date, and it’s one of those scripts that is just good enough that it keeps…like Taxi Driver. Taxi Driver was passed around for about two years, and everyone said somebody should make the script but not us. Then, finally, after enough people had said that, Columbia said, well, why not? And that will happen with Last Temptation.

“If you’re prolific enough,’ Schrader observes, “it all works out. Born in the USA looked dead, and now I’m going to make it. I started Mishima a long time ago. Marty first started wanting to do Last Temptation while he was shooting Boxcar Bertha [1972]… It’s only frustrating for people who commit all of their lives over a period of time to just one thing—it can be very debilitating and almost break your spirit. But if you commit your life to three or four things simultaneously over a period of years, then one always comes up.

“You know, it’s funny, two springs ago there were three films I was supposed to start shooting in the same month: Mosquito Coast with Peter Weir, Last Temptation of Christ with Scorsese, and Mishima. Which one gets made? Go figure. It’s a very peculiar business.”

Postscript: The Mosquito Coast was released by Warner Bros. in 1986. Born in the USA was released as Light of Day in 1987. And The Last Tempation of Christ, revived by Universal Pictures, saw the light of day in 1988.

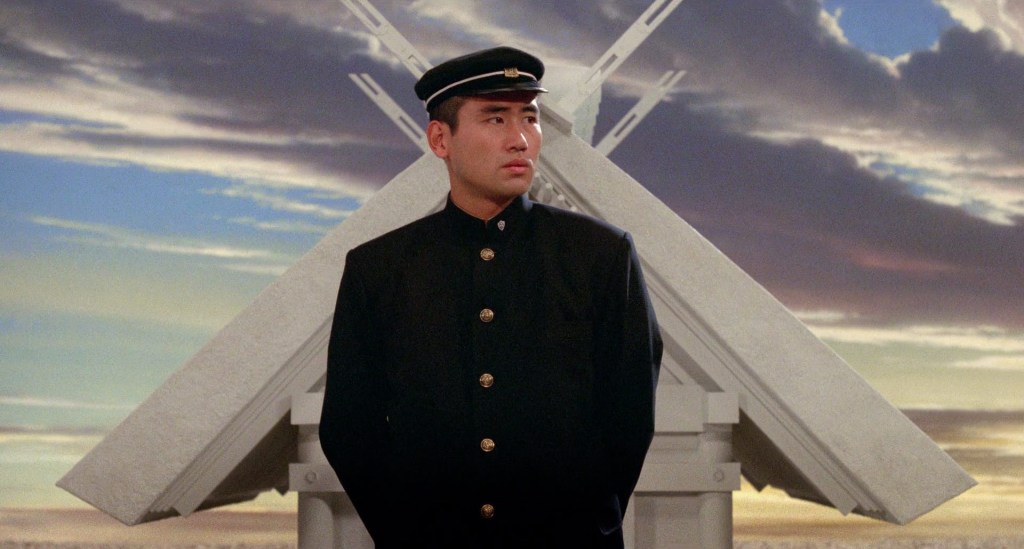

Pictured: Toshiyuki Nagashima. Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters is available to stream on The Criterion Channel and Prime Video.

Leave a comment