Any movie lover can easily name hundreds and hundreds of actors, directors, screenwriters, cinematographers and costume designers. But only a select few title sequence designers have achieved similar recognition. The most celebrated and influential of them all was the late Saul Bass, who began creating iconic opening credits for Otto Preminger in the 1950s and continued innovating with Martin Scorsese into the 1990s. Oh, and he also storyboarded and shot one of the most famous sequences in movie history, the shower murder in Psycho. It was a privilege to talk with this pioneering artist in 1996, on the occasion of a career retrospective at Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts.

See the virgins dance in the temple of doom! See the missionary boiled in oil! See Krakatoa blow its top!

Saul Bass is conjuring up memories of what he calls the “See See See” approach to movie marketing, a technique that faded quickly once this gifted designer set his sights on film title sequences and key art. In the mid-fifties, Bass revolutionized the look and feel of opening credits and movie ads; his influence is enormous, even if his work has seldom been topped. With a string of Otto Preminger pictures (including Carmen Jones, The Man with the Golden Arm, Anatomy of a Murder, Exodus, Advise and Consent, and The Cardinal) and the Alfred Hitchcock classics Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho, this New York native brought a bold, eye-catching, minimalist style to both opening titles and accompanying print ads. His artistry was so self-evident that three major filmmakers made him a key creative collaborator: Alfred Hitchcock called on him to storyboard several sequences in Psycho, including the famed shower murder; Stanley Kubrick used his designs and storyboards for the gladiatorial and battle scenes in Spartacus; and John Frankenheimer had him direct the racing sequences in Grand Prix.

For 20 years, Bass and his wife Elaine (with whom he works in full collaborative mode on film) largely retired from title sequences to devote their time to a series of acclaimed short films, including the Oscar winning Why Man Creates. During this period, Bass also directed a sci-fi feature, Phase IV. In 1987, the Basses returned to the film title world with the opening credits for James L. Brooks’s Broadcast News, and in recent years he and his wife have enjoyed a rewarding collaboration with Martin Scorsese, creating the potent title sequences for Goodfellas, Cape Fear, The Age of Innocence, and Casino.

Bass has no need for false modesty when he discusses his contribution to the motion picture industry. “Within the framework of what was occurring then historically,” he notes, “my work for Otto Preminger [in the mid-fifties] was truly unconventional and groundbreaking. Up until then, the mode of motion picture advertising was potpourri in character; you had many elements of the film—the action element, the love interest, the mystery, etc. It was a montage of elements, the theory of which was that there was something in the stew which would interest you. The idea of boiling it down to one arresting image was very risky. We were saying in effect: This is all we’re going to tell you. That was a pretty radical notion. Of course, most films today are advertised with key art, which usually consists of two or three heads or whatever—the whole notion that I initiated in those days has become institutionalized and is done mostly badly, occasionally well.

“The Man with the Golden Arm, which was the first one, was viewed very skeptically by United Artists, which was releasing the film. Everybody thought that Otto had finally gone over the edge. But it turned out to work extremely well. When The Man with the Golden Arm opened in New York, the symbol had achieved such currency that that’s all they put on the marquee—the arm without the words.”

Bass animated the “twisted arm” advertising symbol to Elmer Bernstein’s jazz score for the movie’s opening titles, and another revolution was born: the reinvention of the film title sequence. “I converted it from a boring list of names, badly lettered, into a dynamic part of the film,” he states, “where instead of the beginning of the title representing the time you had left to rush out and get some popcorn or use the restroom or chitchat with your neighbor, it became part of the film. And that set up the film so that by the time the story began, the audience hit the ground running.”

Along with his work for Preminger and Hitchcock, Bass also contributed memorable title sequences in the 1950s and ’60s for such films as The Seven Year Itch, Around the World in 80 Days, The Big Country, West Side Story (the striking graffiti end credits), Walk on the Wild Side (with its stalking black cat), Nine Hours to Rama, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and Seconds. Since his return to title work, he and Elaine have reached a new level of artistry, with the eerie, abstract play of light and water that opens Cape Fear, the gorgeous time-lapse imagery of budding flowers under lace in The Age of Innocence, and the neon nightmare that follows the opening explosion of Casino.

Bass explains how he and his wife collaborate with a filmmaker. “Once Elaine and I have read the script—or if it’s based on a book, we’ll read the book, as we did with The Age of Innocence—we then think about it and talk to the director and try to understand his underlying intent. To use an old Hollywood phrase, the subtext is the key. The film itself is concerned with events and character, but it all in a sense illustrates an idea that underlies all of that. That’s the part of it that we tend to deal with. We reach for the provocative visual metaphor that will express that basic theme.

‘We have a thorough discussion, and then come up with a notion which we pictorialize, just so there’s something to look at, and then review that with the director. Once we have agreement, we go ahead and do it.

“The nature of the title sequence is usually metaphorical. For instance, in Casino we’re dealing with the underlying notion of the disintegration of the Mafia, a metaphor for the Las Vegas of betrayal, twisted morality, greed, hubris, and in the end self-destruction—in other words, the descent into Dante’s Inferno. The film itself is illustrative of that idea—we simply expressed it as strongly as we could in the opening. We bookend the title with the first shot of De Niro flying heavenward, and in the end with him descending into hell, as the flames come up.”

Bass says the team is thrilled to be working on a continuing basis with Martin Scorsese, whom he considers “one of the handful of truly important filmmakers.” He and his wife receive many requests for title sequence work, but are extremely selective. Bass’s other major area of activity remains corporate trademarks, and over the years the firm of Bass/Yager & Associates has created familiar logos for such clients as AT&T, United Airlines, Minolta and Quaker. Title sequences enable the Basses to sustain their interest in filmmaking without having it dominate their lives.

“I directed a feature for Paramount,” Bass argues, “and it took two years out of my life. And it takes a year, on and off, if you’re doing a short film. You really have to step away from everything else to do it. Here we can do a title, and in a few months we have a nice piece of film, something complete. It’s very rewarding. In the framework of a relatively small amount of time, we engage in all the classic film issues. It’s like a Persian miniature, as against a Velasquez or a Tiepolo.”

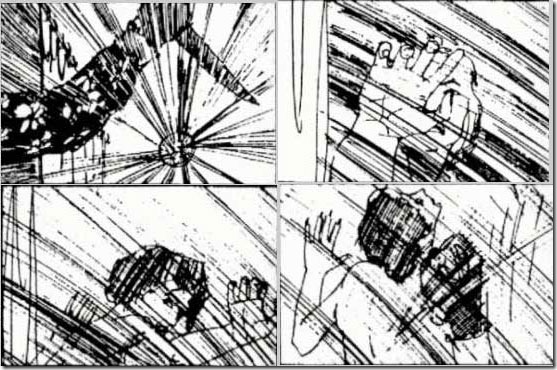

One of Bass’s most celebrated contributions to the art of film remains the chilling shower sequence in Psycho, with its bravura montage of 78 cuts in 45 seconds of screen time. The 75-year-old designer has vivid memories of the experience. “Anybody who worked with Hitch had no doubt that he was in total control of everything that happened on that film. There’s no doubt he was an autocrat, but as far as I was concerned, he was a benevolent autocrat, open to new ideas, generous with his praise, always helpful and supportive. I had a lot to do, but beyond that I just hung around the set as often as I could to watch him work and hear him talk. He asked me to work on several sequences—the shower sequence, Marty Balsam’s murder on the stairs, the revelation of the mother. It was an extraordinary opportunity—his understanding of film was really profound. Hitch was the master, of course, and I was the student. It was the graduate course in film theory I never took. He seemed to like having me around, and I liked being around him.

“Having designed and storyboarded the shower sequence, I showed it to Hitch, and he was initially uneasy about it. It was very un-Hitchcockian in character; Hitch loved the long, continuous shot… His misgivings got me a little bit nervous, too. So I borrowed a camera and kept Janet’s [Leigh’s] stand-in on the set after the day’s filming, put a key light on her, and knocked off about 50 feet of film. Then I sat down with George Tomasini, the editor, and chopped it together, not worrying about finesse, just to see what the effect of these short cuts would be. I showed it to Hitch and he liked it, was very reassured, and he said, ‘Go ahead, let’s do it.’

“Now when the time came to shoot, I was as usual on the stage near Hitch, who was sitting in his elevated director’s chair in his Buddha mode, his hands folded on his belly. He asked me to set up the first shot, as per my storyboard. After I set it up and checked it through the camera, I turned to him and said, ‘Here it is.” And Hitch said, ‘Go ahead, roll it.’ That was an amazing moment. Who else orders on Hitch’s set other than Hitch? But I swallowed hard, I gulped, and said, ‘Roll camera! Action!’ And we made the shot. Hitch sat back in his director’s chair and asked me to set up the next shot as per the storyboard. I did and we went through the same routine. We went through the whole sequence, with him encouraging me benignly, nodding his head periodically and giving me the roll signal as I set up each shot. It was an extraordinary experience.”

Bass also had a major creative role in another big 1960 release, Spartacus. When Stanley Kubrick replaced Anthony Mann as director of the Roman epic, Bass says, “there was a whole change of personnel, and I was the only one who survived it, because Stanley knew my work and he liked what I had already done on the storyboard for the final battle sequence. He asked me to continue working on that sequence, along with a few other things. I designed the set for the gladiatorial training area, which I conceived as a sort of analogy to a circus environment. I was trying to figure out what the gladiatorial school should look like, and I finally saw its relationship to a circus, where you have highly prized animals, carefully cared for, that are potentially dangerous, that you have to keep under control. That’s what led to the circus-like, cage feel of that set.”

Asked about working with the enigmatic Kubrick, Bass declares, “Stanley is terrific. He’s a marvelous monk. He is reclusive. He does an an enormous amount of beard-scratching. I like his obsessiveness, I love it. It’s maddening, but that’s the way it should be. Every time I got irritated, I remember that I’m also obsessive, and everybody who does anything for me gets irritated with me. You know, I did the poster for The Shining and it was maddening. He drove me crazy. But in the course of it, he really pushed me into reaching beyond myself.”

Bass’s most cherished collaborator remains his wife, Elaine, with whom he has been working since the 1960s. “Elaine is a true talent, and she also is a wonderful, beautiful person,” he enthuses. “She is the person I love for what she is and for what she does. She makes an equal contribution to the process. We work in a tandem relationship—we do everything together. The only area she totally controls is music—she’s also a composer. I can’t say enough about how absolutely enriching it’s been, both in a work sense and in terms of the quality of what emerges out of it. We have a terrific time. It’s a great experience to have somebody as a true partner in a process that is so all-consuming.”

Leave a comment