When I met Gus Van Sant in 1991 at New York’s Mayflower Hotel to discuss one of his most acclaimed films, My Own Private Idaho, I was startled to see his star River Phoenix sitting on a nearby couch, strumming a guitar as we talked. At one point, Phoenix chimed in excitedly about how the film was sure to take the top prize at the New York Film Festival. Van Sant patiently explained, “River, it’s not a competitive festival.” Phoenix struck me as a little eccentric, but what a gifted actor, tragically lost to us just two years later at age 23.

In future years, Van Sant would alternate between experimental projects like Gerry, Elephant and Last Days and more commercial outings like To Die For, Good Will Hunting and Milk, the latter two earning Oscar nominations for best picture. He is currently directing the second season of Ryan Murphy’s “Feud,” which centers on Truman Capote’s fraught relationship with New York high society.

“I’m an underground cinema maker working in a legit cinema context. I guess one of my objectives is to just expand cinema, to include other accepted ways of telling a story or understanding an image.”

Gus Van Sant’s mission may seem quixotic in this age of Schwarzenegger firepower and Macaulay Culkin slapstick, but look how far he’s come in just a few years. The Portland, Oregon-based filmmaker first gained a degree of national attention in 1987 when Mala Noche, his $20,000 black-and-white tale of a grocery store clerk’s reckless infatuation with a Mexican street kid, won the Los Angeles Film Critics’ Award for best independent/experimental feature. Two years later, his Drugstore Cowboy went against the grain of the prevailing “Just say no” ethic with its non-judgmental, deadpan look at a hangdog quartet of drug addicts and thieves led by Matt Dillon and Kelly Lynch; the National Society of Film Critics rightly showered it with awards for best picture, best director and best screenplay.

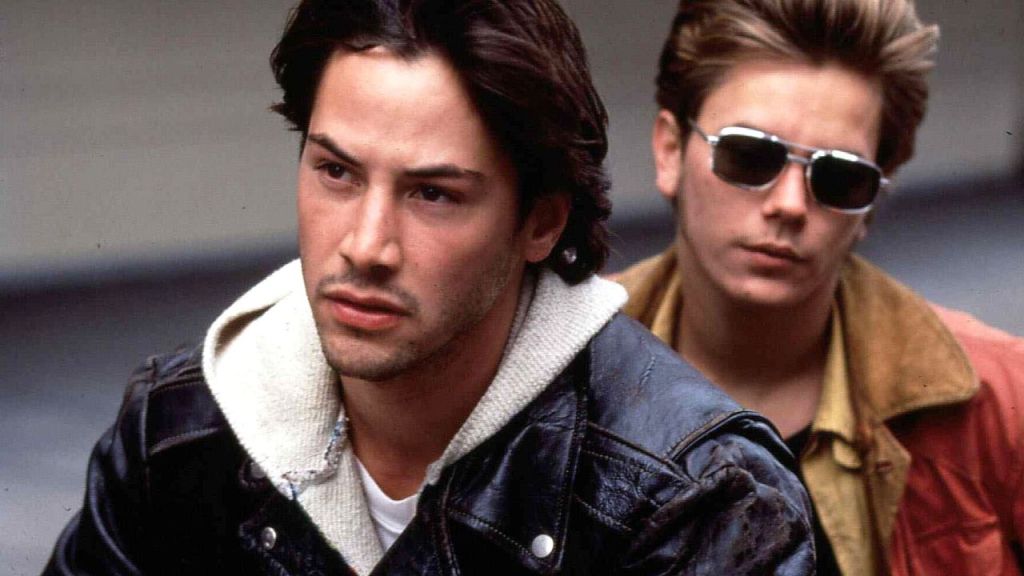

Now comes My Own Private Idaho, starring River Phoenix as a narcoleptic hustler searching for a long-lost mother and Keanu Reeves as the slumming son of Portland’s mayor. Filmed from Van Sant’s first original screenplay, this wry, haunting, risk-taking drama recently debuted in New York to a cluster of rave reviews and long box-office lines.

My Own Private Idaho (which takes its title from an old B-52s song) finds the 39-year-old filmmaker once again offering a fresh, spirited take on characters at society’s margins, told with a poet’s eye for sudden, surreal details. Apart from his lead characters’ unfettered sexuality, the film’s most daring move is surely its modern-day revamping of Shakespeare’s Henry IV (with a nod to Orson Welles’ film variation, Chimes at Midnight), with Reeves’ character, the privileged and rebellious Scott Favor, standing in for Prince Hal, and film director William Reichert playing a Falstaff-like lowlife ringleader named Bob Pigeon. Van Sant’s script even indulges in some quasi-Shakespearean dialogue, updated with references to black leather and lines of coke.

Interviewed at the Mayflower Hotel a few days before Idaho‘s premiere at the New York Film Festival, the soft-spoken, genial writer-director seems naturally pleased with his current film-world cachet. An unexpected guest sits in on the session: River Phoenix, alternately sitting hunched over reading a copy of Film Journal, strumming his guitar, or bounding up to dissect the New York Times ad for Idaho.

Without Phoenix or his fellow teen-heartthrob co-star Reeves, Van Sant’s latest offbeat triumph might never have materialized. Notes the director, “The project was budgeted at $2 million without anyone connected to it. We had apparently gotten this money from a source—I didn’t want to leverage the actors against the production, it’s too Hollywood to do that. I wanted it to be a project people were interested in for its own self. When it looked like we were going into production, I checked with River and Keanu to see if they wanted to do this film and they said yeah. Then our money dropped out, but they came in, which was really good because then we were actually holding a more attractive package and we also had control over it. We were able to get final cut, but it was kind of by mistake. By the time New Line [parent of Fine Line Features] came into the picture, there were a lot more people interested in the film because River and Keanu were involved.”

Van Sant says he partly based Phoenix’s Mike—an emotionally needy orphan who falls instantly asleep in moments of stress—on a similarly narcoleptic figure in George Eliot’s classic novel Silas Marner. The director also modeled Mike after an earlier screenplay incarnation—an inveterate pot smoker who “looked like he had some sort of memory disease, which he used in his favor to control his environment and minimize his responsibility.”

Phoenix recently won the best actor prize at the Venice Film Festival for his portrayal of Mike. In his hands, the director says, “the character became more with it, more three-dimensional and tactile—he was communicating more directly with the audience than the original character as written. The original character was a little more removed, more a zombie.”

Reeves’ character, unlike the vulnerable Mike, becomes a hustler simply to unnerve his well-to-do father, then turns his back on the streets when he reaches 21 and inherits a fortune. “Keanu and I were always trying to figure out why Scott leaves his friends. That was actually the first thing he said to me—he read the script and said: ‘Why? Why does Scott leave, man?’ And this was a really big question—there was a reason in Shakespeare, but there’s not as much of a reason in the modern day. It’s hard to make the jump—when you become the king, you must become the king, but if you just inherit a bunch of money… So we were always trying to figure out who Scott was, because he was such a strange amalgamation of reality and Shakespeare. He’s truly a difficult character to play. Then, eventually, I just thought: I think it’s me. As much as anybody, it’s me.”

Indeed, Van Sant’s background is some distance from the shabbier sections of Portland featured in his movies. The son of a clothing company executive, he was born in Louisville, Kentucky, spent much of his childhood in Darien, Connecticut, and as a teen settled in an exclusive Portland neighborhood. He studied film and painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, and came to Los Angeles in 1976 to work for Groove Tube director Ken Shapiro. Soon after, Van Sant made his first independent feature, a little-seen comedy called Alice in Hollywood. He then left L.A. for New York and a two-year stint in advertising, and eventually resettled for good in Portland.

Van Sant points out that his movies’ concern with people on the fringe is partly a matter of expediency. “It’s just that for the budgets I was working with, they were easier to shoot. I think ultimately that’s the reason those films were conceived about street people, because I just didn’t have the money. It was hard to make a story like Less Than Zero—or My Fair Lady or a space story. Also, I found drama and untraveled territory with all these subjects. There were some films that related to Drugstore Cowboy or Mala Noche or My Own Private Idaho, but there weren’t a lot of them. So you’re making a film about a setting that is a little bit original.”

As proof that his interests range beyond the gritty streets of Portland, Van Sant names some other projects he hopes to film one day. “I wrote a script about high school kids called Mr. Popular, but nobody picked me up on it. I wrote one about corporate executives who commute from Darien to New York City, who are vampires. it’s called Corporate Vampire. I was going to make that at one point for $100,000, with the idea that I would shoot on the trains that I used to ride into work, and in office buildings and in middle-class homes. But that was really stretching the limits of $100,000. Because I had only $20,000, I started to lower my sights. I did Mala Noche, which had only four locations—it was a lot easier to pull off. Drugstore Cowboy was also written with a low budget in mind—I was going to do it for half a million at one point.”

Of all contemporary filmmakers, Van Sant points to Stanley Kubrick as someone he wouldn’t mind emulating. “Kubrick is a really big one for me. He did films that were independent until the studios wanted to give him money, and for MGM he made a real experimental adaptation of Arthur C. Clarke’s novel 2001—he was really going out there. That’s an example of a guy who made a big-budget film that wasn’t particularly commercial, but it made money. He never makes the type of commercial film the studios can snuggle up to. He’s a class act. I relate to him the most, because he has pretty radical concepts and a detailed knowledge of film language, and he uses that knowledge… Each film is really different, he attacks different genres where other filmmakers repeat themselves. He’s pretty avant-garde.”

Asked if he’s astonished by his own progress since Mala Noche, Van Sant smiles. “Yeah, I am. But I don’t have time to be astonished—I have to keep going. I mean, you can only be astonished for so long. Just before Drugstore Cowboy, that was when I was really astonished, because I was going to make a film for $3 million and Matt Dillon had said yes. To me, $3 million was a lot of money, and Matt was my choice of a star amongst a lot of actors. That was where I was really astonished. After that, I think I got used to it.”

Leave a comment