Ken Russell was everything I hoped him to be when I met him in 1987: animated, outspoken, brimming with energy belying his 59 years. (I still remember how he sat with his legs tucked under his torso.) I encountered this veteran enfant terrible of British film during his Gothic phase—he would follow Gothic with the wild horror phantasmagoria Lair of the White Worm.

“I don’t like doing things that are too straight,” says Ken Russell, fully aware of the monumental understatement that’s just passed his lips. Remember, this comes from the director who staged a naked nun orgy in The Devils, who drowned Ann-Margret in baked beans in Tommy, who had Roger Daltry straddle a giant phallus in Lisztomania, who taught Kathleen Turner novel ways to wield a nightstick in Crimes of Passion. Of course, along with that appetite for rude imagery comes a stunning visual and musical sense of film and the ability to create lavish features on astonishingly low budgets. Throughout his career, which ranges from a series of acclaimed BBC documentaries in the sixties and a prolific feature output in the seventies to his latest release—Vestron Pictures’ Gothic—Russell has staked out and maintained his own wild and unique territory.

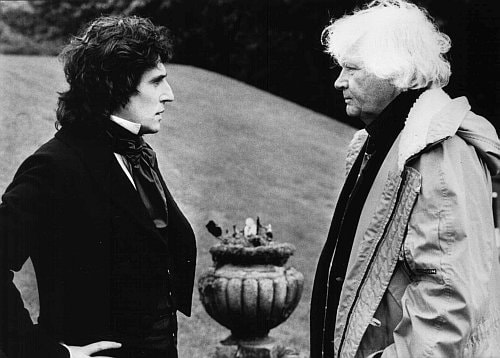

In Gothic, the 59-year-old British filmmaker brings his unbridled sensibility to the summer 1816 gathering of the poets Byron and Shelley; Shelley’s future wife Mary Godwin, whose experiences here inspired her classic horror novel Frankenstein; Mary’s unstable half-sister Claire; and Dr. John Polidori, who would later write the Dracula precursor, The Vampyre. With the fivesome’s crisscrossing sexual attractions, their indulgence in opium and their intense interest in conjuring up the supernatural, this would be no ordinary dinner party. Russell’s film, from Stephen Wolk’s screenplay, quickly crosses over into a hallucinatory realm as the evening turns into a druggy nightmare of the quintet’s worst fears.

Though Gothic gives Russell a rare sustained opportunity to fulfill his penchant for bizarre fantasy, it was the black-comedy aspects of the tale that most appealed to him, he says. “If people are big enough, they can stand a little levity at their expense,” he argues. “It’s probably a healthy antidote for the over-adulation artists have…I didn’t invent this. Thomas Love Peacock, do you know him? He was a Victorian novelist who wrote a series of satires on English society of that period. His greatest book is called Nightmare Abbey, and it’s Byron and Shelley and their girlfriends jumping about on ramparts and getting stoned—and that was written about 1850. So I’m just in a long line of people who’ve not taken them seriously all the time.”

Gothic stars Gabriel Byrne, Julian Sands, Natasha Richardson, and a host of suitably creepy creatures. “We made the film in nine weeks, which is a reasonable amount of time,” Russell recalls, “but when one has to look at all sorts of monkeys and leeches and funny little animals, one’s attention is divided between the leech and the Lord. I remember one time when I had to see these leech people or this snake man or whatever while we were doing this scene I didn’t particularly like. I said to the actors: ‘You do this scene, I’ll give you ten minutes, work it out.’ Opportunity of a lifetime! So they showed me the scene and it was really pretty good. The person who said this is what we decided was not Gabriel Byrne, as I would have thought, but Natasha Richardson. She had a very small part in this scene, and her part was magnified tremendously. She had a sort of sway over the men at lunchtime, she’d sit under a tree and they used to bring her peaches and apple juice and flowers. She was a Cleopatra sort of figure. It was amusing that she managed to build her own part up and nobody seemed to realize how cleverly she’d done it. I admired her for that.”

In spite of this taste of freedom, Russell says he does virtually no improvising on the set. “It’s all very carefully worked out, choreographed. There’s always a bit of room for an idea, an interpretation—but I don’t like wasting time, and there’s no time to waste. I’ve always thought there’s only one way to shoot a scene. Only if there’s a lot of dialogue and it needs to be very fast do I do a sort of classical wide shot, mid shots and close-ups. Generally, the camera lurks around, or people move within the shot like dancers. Nothing’s left to chance—I suppose it comes from my years in the ballet. If people aren’t moving, the camera is.”

Yet Russell eschews storyboards, too. “I’ve got a storyboard in my head,” he asserts, “and there is not much point to drawing it out.” How did this audacious director cultivate his ability to translate his visions to the screen? “I think it was something I was born with—I don’t take any credit for it. I see pretty definite pictures in my head when I want to. I used to listen to music and I couldn’t help but see pictures. Now I see nothing. Whether that’s because I haven’t any more ideas in my mind, I don’t know. But I’d like to think it’s that I’m more selective and I only make my mind work when I really have to. Once I have that picture, usually I have to amend it because it’s too extraordinary—I haven’t got the money to put it on the screen. The only time I’ve had enough money to put the picture in my head on the screen was Altered States, where if I had an idea, we discussed it, drew it up and worked up how it could be done. There was enough money in the budget to buy time to experiment.”

In person, Russell reminds one of a feisty elder cherub, with his shock of white hair, ruddy complexion and ample middle. It’s easy to make the connection between this impish figure and his high-energy pictures. Yet despite their robust style, many of his films center on tortured creative people. How does Russell explain that paradox? “Frustration or fear or pain has an energy, doesn’t it? It has to be expressed somehow—you have to find a metaphor for it. That’s the part of filmmaking I like—I’d rather rely on finding an image to do that than on dialogue. Anyway, as it’s translated from one tongue to another it becomes meaningless—by the time you get to the Chinese version, they’re talking about something completely different. It’s best to do it through pictures.”

Despite the frenzy that frequently overtakes his movies, Russell views his craft dispassionately. “I see films as a discipline—you can’t really allow your feelings of the moment to interfere. I think of a film director as like a surgeon. I don’t know if a surgeon’s ever been asked if a naked female or male, depending on his inclinations, is erotic or just part of the job. There it is lying there and you cut it open. Well, it’s the same with film. If you’re doing what to somebody is an erotic scene, you might find an electrician up in the rafters getting turned on, but to those actually involved—the surgeons and the nurses, if you like—it’s just clinical work that has to be done swiftly and painlessly, with a touch of anesthetic here and there.”

Though he’s shown plenty of stylistic daring, Russell says he’s anxious to change direction. “There’s a very faint chance I might be doing another horror story, and if I do, I’ll try to do it in a totally different way… I don’t know how to do it, but I want to put film in another dimension… We’re still doing the same things we were doing 100 years ago. And I don’t count science-fiction films—the way it’s presented is not stuff of the imagination, it’s just high-tech and hardware. The vision is pretty predictable.

“I think of Virginia Woolf and The Waves—on one page, she manages to convey the childhood of six people and you also get how they’re going to grow up, as well as an afternoon in an English country garden—there are so many layers that words can make. In theory, pictures should be able to do that equally well, but nobody’s found a way to do it. As an art form, film hasn’t made huge advances. I think some of the most interesting advances have been in pop videos. If they had come out in the thirties, everyone would have hailed them as masterpieces, as good as Dali and Buñuel and all that crowd. Some of them are extremely imaginative and very well done.”

Russell speaks wistfully of the “golden days” of the early seventies, “when the American companies had offices in London and were on the lookout for way-out product. That’s all gone—it’s dead and buried.”

Among Russell’s lesser known contributions to the film world are his children. “My oldest son is a film editor, my oldest daughter is a costume designer [her credits include Gothic], and another son is just this moment in Hong Kong directing and producing his first movie. He’s been in Taiwan kung fu movies for the last couple of years. He’s six-foot-eight, and he’s white but he looks Chinese for some reason. He’s a black belt and quite a good actor. He says he can get me a job out there.”

Leave a comment