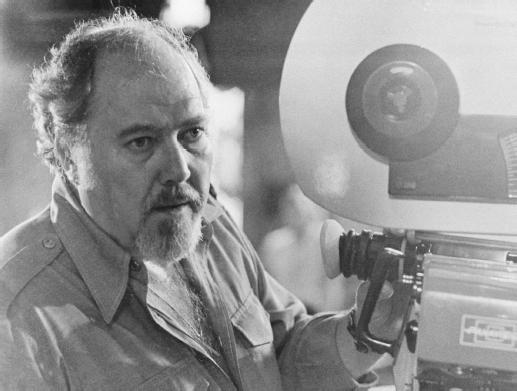

One of my personal pleasures during these pandemic years was revisiting the late Robert Altman’s string of ’70s masterpieces with my good friend Frank de Falco. (Frank’s favorite is The Long Goodbye.) It was a thrill to speak with this great American director in 2000, even if the subject was one of his less celebrated films. Altman was surprisingly upbeat during our conversation, asserting that “I don’t think there’s a filmmaker that’s ever lived who’s had an easier or better shake than I have,” despite his apparent career ups and downs. The end of this Film Journal profile mentions his next project, to be shot in the U.K. That film became yet another career high: Gosford Park, nominated for seven Oscars including best picture and best director.

There’s probably no American director with as much power to attract name actors at bargain prices as Robert Altman. From his Oscar-nominated breakthrough with M*A*S*H in 1970 through his run of ’70s masterpieces like McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye and Nashville, and dazzling ’90s successes Vincent & Theo, The Player, Short Cuts and Cookie’s Fortune, the veteran filmmaker has recruited an impressive array of stars eager to blend into his freewheeling movie ensembles.

Altman’s latest, Artisan Entertainment’s Dr. T & The Women, finds him in Dallas, Texas, with Richard Gere and a virtual harem of female co-stars: Helen Hunt, Farrah Fawcett, Laura Dern, Kate Hudson, Shelley Long, Tara Reid, Liv Tyler and Janine Turner. In this second Altman collaboration with Cookie’s Fortune writer Anne Rapp, Gere plays Dr. Sullivan Travis, a handsome gynecologist with a clamoring clientele of Dallas society women. But, as successful as his professional life is, his home life is a shambles: His wife Kate (Fawcett) has suffered a mental breakdown which has left her with the impulses of a child; his about-to-be-married daughter Dee Dee (Hudson) is harboring a potentially explosive secret; and Dr. T’s new companion, golf pro Bree (Hunt), has him blindsided by desire. The good doctor’s estrogen-filled existence will never be the same once his female troubles converge in the movie’s startling climax.

“I think he’s been looking at women from the wrong end most of his life,” Altman jokes about his dashing but frazzled hero. “He’s kind of an idealist, not a realist. You would think a guy like that would be a realist, but he’s one of these men who feels that women should be taken care of. We could easily call this The Man Who Loved Women Too Much.”

Altman says the response from women to his latest take on the sexes has been particularly strong. “They love it. Women get it. Most men look at it as kind of a dirty joke, at first. Edgar Doctorow, for instance, saw this picture and he said, ‘I think it’s the best thing you’ve done, I love it, but God, I’m glad Helen didn’t see it’—that’s his wife. I said, ‘Why?’ And he said, ‘Oh, women are going to hate this.’ But women are our largest audience, they’ve been our best audience. They get it. Men don’t quite get it, or they get it maybe after the fact. But when we start into it, the dirty laughs come from the men… I think men and women really see this differently. That’s part of the reason we went into this arena—most men don’t know what happens in a gynecologist’s office. It’s not that they mistrust their wives, it’s just that they don’t understand, and consequently they’re a little suspicious. And if the doctor’s good-looking…”

Altman’s films have often plunged audiences into very specific American subcultures, and Dr. T & The Womenis certainly a prime example, with its intimate look at Dallas’ moneyed class. Yet the director insists that the characters in his new film “are like every American and French person and English person and German person and all the Western cultures. They’re all the same. They all have their own different foibles. In Dallas, there are no mountains and no shore, and there’s not a lot to do but shop. But I don’t think that’s demeaning—I think that’s who they are and that’s the way they express themselves. You go to Los Angeles or Chicago, and you’ll find the same strata of people. Dallas was kind of easy because you have the golf and benchmarks like Dealey Plaza and the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders. But it’s just another movie. It’s certainly no different than what we did with Nashville, or in A Wedding in Chicago. You take a certain part of society and you immerse your story into that and use that as the dressing.”

The proprietors of a certain Dallas shopping mall won’t soon forget one key scene, in which Fawcett removes all her clothes and cavorts in a fountain. (With typical visual mischief, Altman then pans over to a Godiva Chocolate storefront.) “She’s a very brave actor,” the director says of the former ’70s pinup. “I can’t say enough about her. I hear all these things: ‘Oh God, she’s difficult.’ I have no evidence of that. But if you get into the press and get too much publicity, it eats you up.”

Altman is also effusive in his praise for leading man Gere. “He’s just excellent. I can’t imagine anybody doing a better job… He just was it to me. People like him, women like him, he’s charming. We never thought about anybody else [for the role].”

The director’s fondness for actors helps explain his appeal to A-list talent. “I don’t think anybody realizes the soul and the spirit that actors have,” he declares. “They may be a little off the wall, but they’re very courageous and I don’t understand how they do what they do. I just love it. By the time I get a film cast and we get ready to go, I don’t have a lot of work to do other than keeping it inside whatever the boundary is. But they do the work and the creating.”

The family atmosphere on an Altman set extends beyond the workday, as the director always makes a point of inviting his performers to join him in watching dailies. “That’s just treating them with some dignity, because they’re the ones that are doing the work,” he contends. “Why in God’s name would you not show them what they’ve done? Unless you don’t trust yourself. Some actors, like Julie Christie and Tim Roth, won’t see themselves, and if they feel that way, that’s fine. But I encourage everybody to see dailies.”

With so many ensemble films to his name, the list of Altman alumni is enormous. “We just had the 30th anniversary of M*A*S*H and the 25th anniversary of Nashville. Both in L.A. and New York, they had a summer of showing my films of the ’70s, and it was just great to have all these people come together. It’s like a high-school reunion.”

Some Altman observers lamented his lower profile in the 1980s (despite worthy efforts like Streamers, Secret Honor and Come Back to the Five and Dime Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean), but the director insists he’s never really seen a rough patch. “I don’t think there’s a filmmaker that’s ever lived who’s had an easier or better shake than I have,” he proclaims. “In the last 30 years or more, I have never been without a film, and I’ve never had a film that wasn’t of my own choosing. I read about the little films or the theatre that I did when times were tough for me. Well, times weren’t tough for me! Those are things I chose to do. I’ve never been interested in doing blockbusters. Everything is judged by how much money it makes. Porky’s becomes a lauded film because it made so much money. But I don’t know how to do that—a film like that, I’d be afraid I’d be late for work. I’ve not had any bad times. Nothing’s easy, because I have to work on a lower budget, but that’s all right. I don’t mind that—I like it, as a matter of fact.”

Asked about his growth as a filmmaker, Altman reflects. “You get more facile, but I don’t think the art gets any better. What I would call the soul or the art of the film, that doesn’t increase. That’s what your m.o. is, that’s what you do, and then you learn not to waste as much time. But if you get too clever, you’re in danger of losing the art.”

Altman is now preparing to round up a largely British cast for an untitled film to be shot in the U.K., about the end of the indentured servant culture in the 1930s. Having recently turned 75, his energy and enthusiasm are undiminished. “I’m chronologically 75,” he notes, “but I still feel like I’m 32 or whatever age it was I started thinking I knew who I was. I don’t have any intention of stopping until something cuts me down. But that’s going to happen to everybody.”

Leave a comment