The 1999 comedy Bowfinger gave me the opportunity to get on the phone with both Steve Martin and Frank Oz, reuniting 11 years after their memorable farce Dirty Rotten Scoundrels.

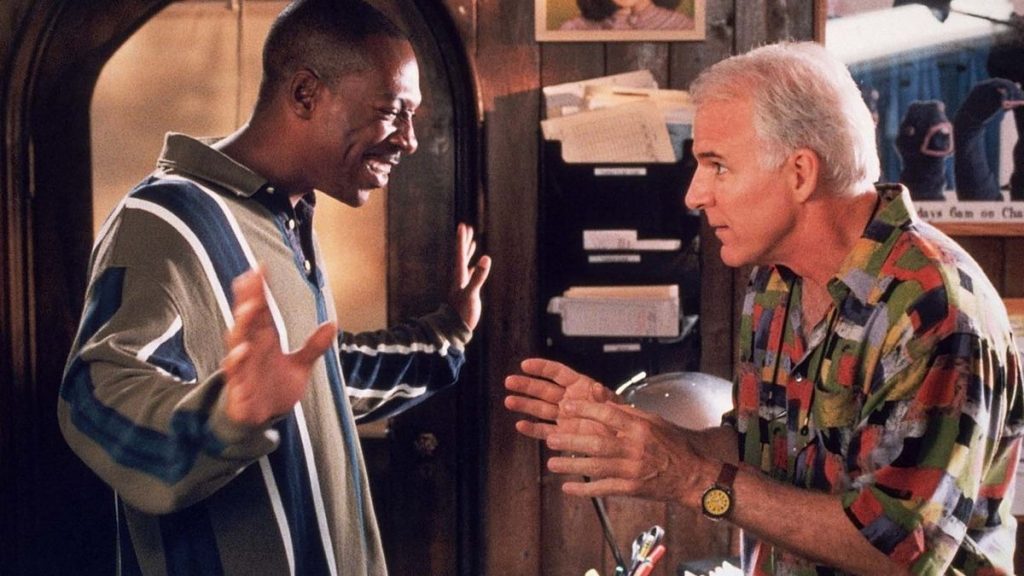

Anyone who’s ever tried to break into the movie business has probably crossed paths with a Bobby Bowfinger. As played by Steve Martin in the comedy of the same name, Bowfinger is a desperate and destitute would-be producer-director who can’t even afford a cell phone and whose biggest claim to fame is an industrial short called The Yugo Story. But Bowfinger has come into possession of what he believes is a surefire action script (written by his Iranian accountant), and he’s determined to nab one of the top stars in Hollywood, Kit Ramsey (Eddie Murphy), for the lead. Rebuffed at every turn, the low-rent producer hatches a scheme that’s bizarre even by L.A. standards, setting up hidden cameras to film the paranoid star “in action” with his motley ensemble of players. Written by Martin, directed by Frank Oz and produced by Brian Grazer, this delightfully zany tale of the Hollywood fringe, also featuring Heather Graham, Christine Baranski, Jamie Kennedy, Terence Stamp and Robert Downey, Jr., opens August 13 from Universal Pictures and Imagine Entertainment.

“I think there’s always something sympathetic about outsiders in Hollywood who are struggling against the size of everything,” Martin declares. “I remember doing it myself. I was in my early 20s and just wondering: How do you get in? There was no ‘Entertainment Tonight’ then to tell everyone how it worked, no E channel. Show business was a mystery.”

Director Oz, who began with Jim Henson’s Muppet troupe and has gone on to direct such hit comedies as Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, What About Bob? and In & Out, also recalls his early days as a struggling filmmaker. “Thirty-five years ago, Jim did this short film, Time Piece, which got an Academy Award nomination. We spent about a year doing this small film—the four or five of us, we were kind of a fringe doing that stuff. Jim and I would go to Filmmakers Cinematheque, watching the Andy Warhol and Stan Brakhage stuff, and we were in a two-room office with three other guys. And so we not only met fringe people, we were fringe people. Bowfinger brought back those memories.”

Martin says his character is “a pastiche of many people I’ve known, and fictional characters, too….I once knew a producer who was always on the edge. He had some success, but he kept a big fishbowl on his desk with razor blades with people’s names on them, people who he felt had crossed him. There’s always this little-guy-against-the-big-guy syndrome that they have. I don’t think Bowfinger has that, but many outsiders do—they feel they’re being crushed by giant corporations.”

The veteran comedy star says that “the germ of the germ” of his latest project came to him during the making of one of his earliest films, the lavish 1981 period musical Pennies From Heaven. “We had all these beautiful sets and costumes, and I realized you could shoot two movies at the same time if you wanted to, if you just had a different script. After you finished one take, if you wrote the scripts cleverly enough, then you’d just shoot the other scene. It was a fantasy, but that was the beginning of it, on some abstract level.”

Bowfinger itself became a different movie when producer Grazer came up with the idea of casting his friend Eddie Murphy as the high-strung Kit Ramsey (and his nerdy double, Jiff). As Martin recalls, “My reaction was: ‘Do you think he’d possibly do it? I think he’s great.’ It meant a big rewrite, because it was written for a white person. But to have him is such a plus that you could only say: ‘Yeah, great idea.’ And, actually, it turned out to be a fantastic idea, because my original conception was a Keanu Reeves type actor, sort of low-key, and this gave the movie so much more life.” Martin reveals that he had several discussions with Murphy that impacted on the script—a necessity, he notes with a laugh, “because I was essentially talking about a culture I had no relationship to.”

Oz feels Martin and Murphy have more in common than their public personas would lead you to expect. “It’s always interesting to me that people who are very funny and very brilliant like Steve or John Cleese or Bill Murray are—not always, but often—very reserved and thoughtful and shy, and keep the energy for the take. And that’s what Eddie was. And very, very smart, too.”

Oz first met Martin some years ago as a fellow performer (playing the celebrated Miss Piggy, among others) in The Muppet Movie. Bowfinger marks the fourth time he’s directed the comedy star, following Little Shop of Horrors, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and Housesitter. “I just go where the fun is,” Oz remarks, “and we’ve had a lot of fun doing the movies we have. Steve writes a script and asks if you want to do it, and I say: ‘Yeah, sure.’ We don’t say: ‘I love the script just as it is, let’s do it.’ He and I both know the script isn’t where it should be, but we both have faith in each other that by working together, especially Steve as the writer, we’ll make it better.”

The director says he’s seen a change in Martin over the years. “As a human being, he’s opened up more, but as a performer, I think he doesn’t perform as much, he just is more….He’s become more comfortable with just being who he is on the screen.”

“I think that’s true,” Martin agrees. “I started as a big, manic comedian. There are a lot of transitions you have to go through to get to, say, The Spanish Prisoner [Martin’s highly praised dramatic turn in last year’s David Mamet art-house success].”

As for what Oz offers him as a director, Martin notes, “First, he brings a stylish look to the movie, and a lot of comedies look like junk. When you make these movies, you have to think about, ‘What is it ten years from now?’ Because if it’s a junky-looking movie, it may not have any staying power. And he’s really good with script—he doesn’t let me cut the jokes that I’m bored with. Also, as a director he’s very clean, meaning he doesn’t get in the way of the humor. He knows the humor comes first and he’s always thinking about what the audience knows when.”

Oz also admits to a bit of a subversive streak. “I look for things that are edgy, but I try to make them acceptable to a lot of people. It’s very easy to make an edgy project for a small niche—it’s like making it for your friends. It’s hard to do a major motion picture and make homosexuality [as in In & Out] a subject where people will watch and laugh and accept. It’s easy to do a little film about the movie business and blacks and whites, making it edgy for a small group of people, but the hard thing is to do it for a large group of people and still have them laugh at the Ku Klux Klan jokes without it being threatening.”

Perhaps the riskiest aspect of Bowfinger is the Kit Ramsey character’s allegiance to Mind Head, a secretive and powerful self-help institution catering to celebrities, which some observers have noted bears a resemblance to the controversial Church of Scientology. Oz speaks carefully when asked about the similarity. “I know there are some concerns from Scientologists,” he notes. “But, on or off the record, I feel the same way. We’re making fun of people in an equal-opportunity sense. We’re making fun of this religion—not this religion being Scientology. Scientology is one of the possibilities—it could be the Moonies, it could be the Catholic Church, Judaism, it’s just a religion that has power over this particular guy, because that’s what the storyline needed. But, really, we’re making fun of ourselves—we’re making fun of these idiot directors, I’m making fun of myself. We’re making fun of producers, of actors, of blacks, of whites. We’re just making fun of everybody, and hopefully everybody who’s being made fun of has a sense of humor about it.”

As the writer, Martin, too, contends that he’s not honing in on Scientology per se. “The whole bit is a pastiche of things I’ve seen in Hollywood for the past 25 years. It’s a little of this, a little of that. There are certain aspects that, yes, are consistent with Scientology, and there are other things that aren’t consistent but are consistent with something else.”

Oz and Martin both seem pleased with what they’ve accomplished, but each is continuing to look for new challenges. Says Oz, “I’m very fortunate in that I get all the best comedy scripts. But I never wanted to be only a comedy director. I always wanted to be a theatre director, and I came in through Jim Henson who supported me and then I was offered these comedies. And the scripts of the comedies I’ve been offered are better than the scripts of the dramas I’ve been offered. So I go with the better script every time. But I’m not satisfied, because I always like to do other things. I’d love to do a comedy and then an action film, and then a comedy and a psychological thriller. I’d like to go back and forth, but I go where the really good scripts are. I’d rather do a really terrific comedy than a so-so drama.”

Martin, meantime, has not only expanded his range as an actor in recent years, but regularly contributes witty pieces to The New Yorker, published a collection of his offbeat comic vignettes called Pure Drivel, scored a major success off-Broadway and in other cities with his first play, Picasso at the Lapin Agile, and is now working on his first novella. Declaring “I don’t just want to be an actor,” Martin says he’s devoting more and more of his time to writing. “I have a luxury,” he reflects. “I just write what I feel at the time. I don’t consider myself a screenwriter first or an essayist first or a novelist first or a playwright. I just do whatever I have the ideas for. I have maybe one or two film ideas, but I’m not actively pursuing them. I’ll do them when the time is right. Like Bowfinger—I had the idea for over ten years, and I thought, ‘OK, now is the time.’”

Fans of such Martin scripts as Roxanne, L.A. Story and the new Bowfinger may be disappointed by that news, but it’s clear this one-time “wild and crazy guy” has found an enviable balance in his life. If Martin can juggle so many careers so adroitly, there may be hope for the Bobby Bowfingers of this world after all.

Leave a comment